Blog Nº 30

“I could recognize him by touch alone, by smell; I would know him blind, by the way his breaths came and his feet struck the earth. I would know him in death, at the end of the world.”

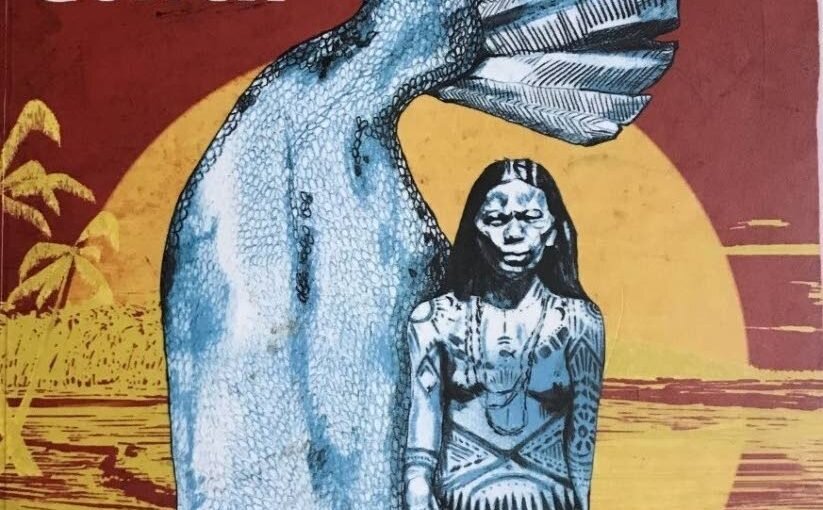

I have wanted to read The Song of Achilles ever since being blown away by another of Miller’s novels, Circe. Much like how Circe is an imaginative homage to the goddess encountered by Odysseus in Homer’s The Odyssey, The Song of Achilles is an original take on The Iliad, one of the best known stories in the West. The heroes and villains of the Trojan War are brought to life like never before in this story of love, friendship, power and violence.

The Song of Achilles is narrated by Patroclus, an awkward young prince living in the age of Greek heroes. Exiled to the court of King Peleus on the small island of Pthia, he strikes up an unlikely friendship with Peleus’ son, the golden boy Achilles. As the two boys become young men, their bond develops into something deeper, despite the displeasure of Achilles’ mother, the sea goddess Thetis. Over the years, their companionship grows stronger and the two boys are still enjoying their carefree youth when Helen of Sparta gets kidnapped. This turn of events means that Achilles must go to fight a war in distant Troy to fulfil his destiny. Torn between love and fear for Achilles, Patroclus goes with him.

The relationship between Achilles and Patroclus is highly significant in all stories relating to the Trojan War. In The Iliad Homer describes their relationship as deep and meaningful but never says explicitly that it is a sexual relationship. However, they were represented as lovers in Greek literature during the archaic and classical periods and it has been debated and contested ever since. Strong bonds between men was a custom in Ancient Greece, and this relationship could be intellectual, political and sometimes sexual. Miller has chosen to make their relationship deep and meaningful on many levels including sexual, and as such has created a moving, heartbreaking story.

As Patroclus narrates the novel, we are aware of his awe and admiration for the beautiful Achilles from the moment he arrives in Pthia. After several stolen glances and chance encounters, the pair finally speak, and a tentative friendship begins. In fact, they are good friends for a long time before anything else develops between them, though it’s clear they both desire each other. Miller’s smooth prose conveys their relationship as sexy and intense as well as thoughtful and sensitive, making the reader extremely emotionally invested in their bond, particularly as the danger of war looms.

Miller spent ten years researching and writing this book but has succeeded in crafting a seemingly effortless narrative that takes all the key elements of The Iliad and other stories to create a highly affecting version of Achilles. Where once stood the callous, cold superhero is now a man with depth who can be kind as well as godlike. He is not just a hero but a lover, a friend, a son, a father, a husband and most importantly, a normal human being. This makes the reader all the more emotionally engaged in the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, because it is clear they are the only people for each other.

The Song of Achilles is an epic novel, with several years passing before the ten year long Trojan War. I enjoy epic novels because you really become invested in the characters, their development and their world. A key moment in the book is when the pair realise that Achilles must go to Troy because it is decreed in a prophecy with a heartbreaking end. As a reader who has been following their story since boyhood it is natural to be as sad and fearful as Patroclus about this. Though for years they agree to fight the battles but purposefully avoid the terms of the prophecy, in the end it is their love for each other that eventually sees it fulfilled with all the tragedy as befits an Ancient Greek tale.

This book is a vividly atmospheric, enthralling and emotional read which sees the deepest human connections challenged against a backdrop of violence, politics and power. It is a joy to read this depiction of Achilles and Patroclus’ relationship – it is certainly a poignant story about love and friendship. I would highly recommend this book to anyone and everyone!

Happy reading,

Imo x