Blog Nº 37

“It’s necessary to have wished for death in order to know how good it is to live.”

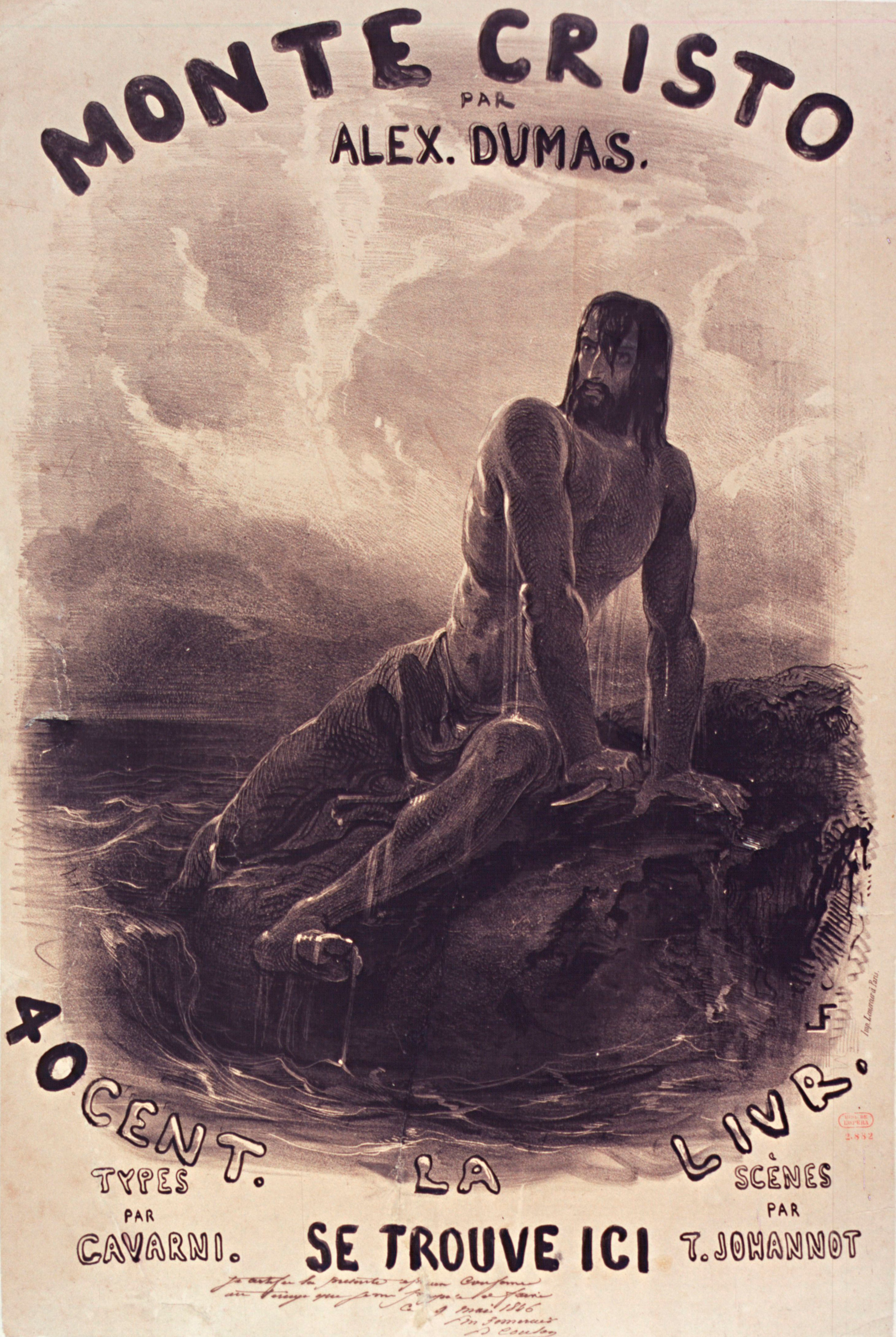

The Count of Monte Cristo has overtaken Gone With the Wind as the longest book I have ever read, coming in at 1,243 pages. This did not stop me racing through it because it is one of the most engaging, clever and thrilling novels I have ever read. It certainly deserves its reputation as one of the greatest books of all time. A story of adventure, hope, justice, revenge and forgiveness, The Count of Monte Cristo will whirl you away into a turbulent period of French history and will stir up all your emotions as you follow one man’s struggle for almost thirty years.

Our story begins in the French port city of Marseille in 1815, and the novel’s protagonist is the young, dashing and thoroughly good Edmond Dantès, who at just nineteen years old is a talented sailor. Despite coming from humble beginnings, Edmond could not be happier with life. He is engaged to the beautiful Mercédès and he is first mate of the Pharaon, owned by the kindly shipowner Morrel. On the day of his wedding, Edmond is falsely accused of treason and Bonapartism and is sent without trial to the island fortress prison off the coast of Marseille, the Château d’If.

While imprisoned in the darkest dungeon of the prison Edmond befriends Abbé Faria, a fellow prisoner who had been trying to tunnel out of the prison when he arrived at Edmond’s cell. From Edmond’s story, the Abbé is able to deduce who falsely accused and turned in Edmond for their own gain – namely, jealous love rival Fernand Mondego, envious crewmate Danglars and the double-crossing magistrate De Villefort. During their dark years of imprisonment, the Abbé teaches Edmond history, languages, science, literature and more, but most importantly tells of a vast wealth of treasure on the small uninhabited island of Monte Cristo close to the Château d’If that he believes exists from intense historical research. Together they plot their escape, but when the Abbé becomes too ill and is on the verge of death, bequeaths all the treasure to Edmond. After 14 years of wrongful imprisonment, Edmond is able to escape the hellish prison and to his astonishment, discovers that the Abbé was right about the treasure when he arrives at Monte Cristo.

Fast forward ten years and Edmond arrives in Paris from the Orient, unrecognisable as the mysterious and infinitely wealthy Count of Monte Cristo, secretly set on exacting revenge upon Fernand, Danglars and De Villefort, who have all achieved high levels of success, wealth and status, in part due to their betrayal of Edmond. As the novel progresses it becomes clear how the Count has spent the last ten years patiently and masterfully doing his research and setting up his plan, which will send the reader into a fever pitch as the Count embeds himself in the lives of his enemies. The Count of Monte Cristo is an interesting look into the inner morality of man, as even those who have endured much suffering at the hands of others can still wage a battle within themselves about the choice between revenge and forgiveness as emotions run high and old wounds are reopened.

This novel spans from 1815 to 1839, and Dumas should be praised for keeping up such a fast-paced and involving narrative, despite the complexities of the story and the many strands of the tale that make up the story of Edmond. Interestingly, the bones of the novel are taken from the real-life story of shoemaker François Picaud, who was denounced by his friends as an English spy and imprisoned shortly after becoming engaged to a young woman named Marguerite. After serving part of his sentence under house arrest, his master left all his money to Picaud and informed him as to the whereabouts of a hidden treasure. Unlike Dantès, Picaud went around killing all of his enemies but it is clear how inspired Dumas was by this story, and how skilled he is as a storyteller to bring the story to life and adding in so many nuances, links and plotlines. A key shift is the Mediterranean angle that Dumas gave to The Count of Monte Cristo, by starting the novel in Marseille. The idea of the Mediterranean as the exotic and intoxicating meeting point between the cultures of Europe and the Orient fascinated French authors during this period, and this novel uses the character of the Count to fulfil many Orientalist tropes. The Count has a colourful, rich and vibrant sense of dress, interior design and always lays out an exotic feast for his guests. His household staff include the Nubian mute slave Ali and his devoted companion Haydée, a beautiful Turkish girl he rescued in Constantinople. Additionally, his knowledge of the Orient (as idealised by Europeans during this time) and his mastery of languages lead many of the other characters to believe he must be from the Orient, if not for his very pale skin, which unknown to them is a result of his long period of imprisonment. Many come to the conclusion that he must be from a point between Europe and the Orient like Malta, when in fact he is French through and through.

What I find the most satisfying and intelligent about The Count of Monte Cristo is the fact that despite the Count’s plot to bring down his enemies, he is still only the indirect avenger of his misfortune. In fact, it is their own past misdeeds that destroy the ‘victims’ Danglars, De Villefort and Fernand, all of which are simply uncovered and exploited by the Count. Furthermore, having been educated by the Abbé Faria and armed with limitless wealth, Dantès is able to come back as an instrument of divine justice in the guise of the Count, though that still does not stop him being plagued by insecurity and doubt as his plans take hold. Another interesting perspective is that the Count and the Abbé are early forerunners of the ‘detective’ figure in literature. There are certainly some Holmesian aspects to the novel. For example, the Abbé’s deduction of who betrayed Edmond and why, simply from Edmond’s retelling of the tale. Secondly, the logic behind the Count’s plans only becoming visible to the reader later on while the Count has been the master of events all along. Haydée is a key example. While at first perceived to be simply the Count’s exotic young companion acquired on his travels, she is also the daughter of Ali, Pasha of Janina, a man whom Fernand secretly betrayed to acquire a huge fortune and earn a misplaced military respect in France. Therefore, she is revealed as the proof that would help to bring him down.

The Count of Monte Cristo is an exciting and moving adventure, and after following the Count for so long it is satisfying to see good winning out over evil. However, it is hard not to be struck by the sense that despite the Count’s fulfilment of his plan and achieving the rare opportunity of obtaining education and limitless wealth as a result of his imprisonment, no amount of money can replace a lost life and destiny. Though able to find some peace, the Count will never be able to get back the happy life he once lived as Edmond Dantès, the young sailor with little to his name in terms of money or education, but who had his whole life ahead of him and was surrounded by love and joy. The true tragedy of the novel is that Dantès’ life ended the moment his so-called friends turned him in, and his struggle to forge a new life as the Count will still always be secondary to who he once was.

Happy reading,

Imo x