Blog Nº 19

“The world is changing: I feel it in the water, I feel it in the earth, and I smell it in the air.”

I have now completed my third foray into Middle-earth by continuing on with the next LOTR instalment, The Two Towers (TTT). This has to be my favourite so far; Tolkien’s storytelling reaches a new peak now that the Company has splintered. Sauron’s power is growing, and this is represented in the land becoming ever more menacing and treacherous. And yet, the burning hope of the fellowship cannot be dimmed, even when separated from one another. This tale captivates with even more mysterious and vast landscapes filled with strange people, all which bring us closer to the horror of Mordor where the One Ring must be destroyed.

TTT is split into two parts. The first deals with those in the company who Frodo and Sam left behind, namely Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli. Their first mission is to rescue Merry and Pippin who were taken by orcs at the Falls of Rauros. Along the way they encounter old friends and new allies, all intent on bringing the evil wizard Saruman to his knees. Lurking in Isengard, Saruman is in league with the dark lord Sauron, so the group knows that this victory will help Frodo and Sam from afar in the completion of their wretched quest.

In the second part, we return to Frodo and Sam who are continuing on to Mordor. A key player in this section is Gollum, who has been shadowing the pair of hobbits for miles and miles with the aim of reclaiming the Ring for himself. Through some clever manoeuvring from Frodo, Gollum remains unaware of the true nature of the mission and ends up being their guide to Mordor. He can never quite be trusted, making the long journey across such desolate lands even more uneasy. As the burden of the Ring weighs ever more heavily on Frodo, it is up to his trusty and loyal companion Sam to keep his master safe from the dangers looming on all fronts.

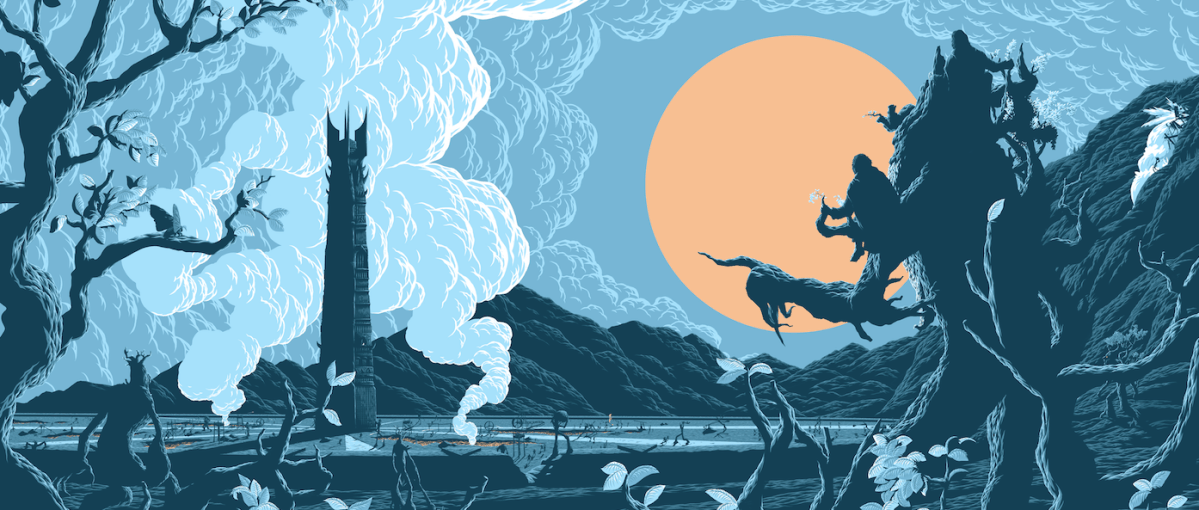

One particularly magical happening in TTT is the introduction of the Ents, who are without a doubt my favourite Middle-earth creatures. Guardians of the forests, Ents are an ancient race of tree-like beings, most likely inspired by longstanding folklore tales of talking trees. ‘Ent’ comes from the Old English word for giant, indicating that despite their ability to blend in with the forest, they are much larger than regular trees. Merry and Pippin are fortuitously rescued by Treebeard, the oldest of the Ents and indeed the oldest living thing in Middle-earth. Confirming what he already feared, Merry and Pippin inform Treebeard of Saruman’s orc army desecrating the forests to provide fuel for their war machine. This leads to a particularly wondrous event, an ‘Entmoot’. That is, a large meeting of the Ents – in this case to determine the best course of action against Saruman.

I like the Ents because they are patient, kindly, wise and methodical and because despite all this, you should never underestimate their strength or power in their duty as tree protectors. Treebeard and the other Ents successfully march on Isengard, entrapping Saruman in Orthanc Tower and simultaneously reuniting Merry and Pippin with Gandalf and the others. I have developed a serious soft spot for these magical trees with booming voices; the only sadness is that they have lost their ‘Entwives’ and are yet to discover their whereabouts. I like to think that they did eventually reunite.

Another standout section of the TTT comes in part two with Frodo and Sam. They are struggling to find their way to Mordor until Gollum offers to be their guide. The closer they get, the more bleak and menacing their surroundings become, indicating the cruel grip Sauron’s kingdom has over its neighbouring lands. As I have said previously, Tolkien is truly a master of language. Never have I been made to feel such dismay, hopelessness and distress from descriptive passages alone. One poignant chapter is ‘the passage of the marshes’, in which Gollum leads the two hobbits across the Dead Marshes to avoid being seen by orcs on the main path to Mordor. The way Tolkien describes the marshes makes it seem as though goodness and light have long forgotten this vast and sinister place. One foot wrong and the hobbits would flounder and sink, joining the ghosts of the many soldiers who were slain there long ago. Tolkien emphasises the foul stench of the marshes and the haunting floating lights that surround them on their difficult path across. There is no sound or sight of a single living thing in these marshes or overhead, making our three characters seem utterly and completely alone in this desolate and unwelcoming land. Immediately I thought that Tolkien must have been inspired by his time fighting in the trenches in World War Two to create this bleak and frightening landscape.

I also discovered that Tolkien’s time in the industrial Black Country of the English Midlands was an inspiration for Mordor and its surrounding lands. This is clear to see when comparing the explicitly evil, industrial land of Mordor, which has a cost of environmental decay and destruction, with the light, homely and nature-abundant Shire, which is more akin to some of England’s picturesque rural counties.

At the end of The Two Towers we are still unsure whether Frodo’s quest will ever be completed and what will become of all the members of the fellowship, and indeed of Middle-earth itself. TTT has been a thoroughly enjoyable, exciting and suspenseful read; I am anxious to get going on The Return of the King so I can see this long and treacherous journey come to an end, hopefully with the conclusion that goodness always prevails…

Happy reading,

Imo x