Blog Nº 17

” Faithless is he that says farewell when the road darkens”

After finishing The Hobbit, I was more than happy to continue on my adventure through Middle-earth by delving straight into the first volume of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Fellowship of the Ring (TFOTR). I thoroughly enjoyed this novel as we start to see the consequences of Bilbo Baggins taking the One Ring from Gollum in The Hobbit playing out with ominous effect. More mature than The Hobbit, which Tolkien wrote for his children, TFOTR wrestles with themes of greed, power and violence as its heroes fight to keep the all-consuming darkness at bay. And yet the warming moments of humour, friendship and courage which often prevail against the gloom of evil keep the reader faithful in the power of good and fully ensconced in this exciting adventure.

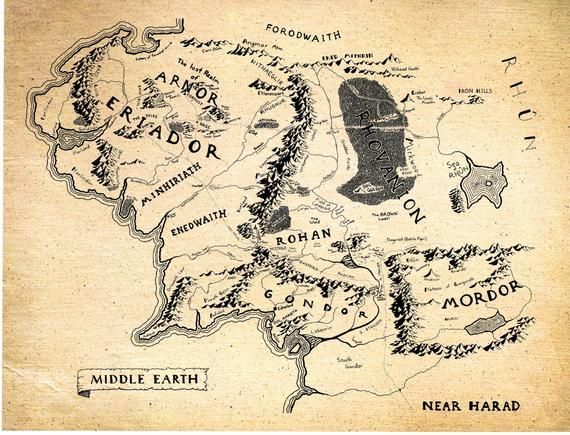

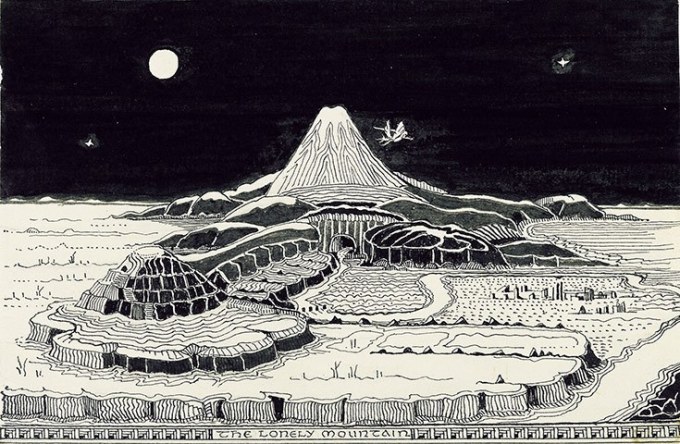

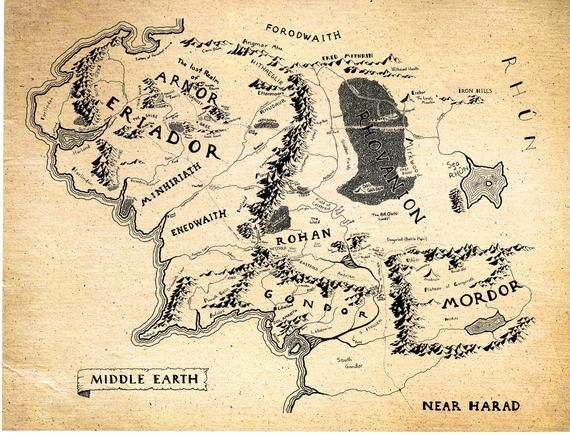

Set 60 years after The Hobbit, TFOTR deals with the fallout of Bilbo’s innocent taking of a gold ring from the creature Gollum. We discover that years ago, the dark lord Sauron created a set of Rings to give to the rulers of Men, Elves and Dwarves. However, Sauron deceived them by secretly making another, the One Ring to rule them all. Lost and forgotten about, this is the extremely powerful and dangerous Ring that came to be in Bilbo’s possession, unbeknown to him. To stop Sauron regaining the Ring and therefore bringing Middle-earth into an era of evil and darkness, a great quest must take place to destroy the Ring in the place of its creation, the fires of Mount Doom in Mordor. This is a mighty challenge which is why a select few, ‘the fellowship of the ring’, are chosen for the task.

The nine members are: Frodo Baggins, his gardener Sam Gangee, the wizard Gandalf, the elf Legolas, the dwarf Gimli, the men Aragorn and Boromir, and the two young hobbits Merry Brandybuck and Pippin Took.

As had been proven by Bilbo, the corrupting influence of the Ring works much more slowly on hobbits as they are truly good creatures less easily swayed by greed and lust. This is why it is Frodo who bears the Ring while the others act as his guides and protectors. Met with much peril and evil along the way, the group also become firm and loyal friends. Although they encounter much danger and loss, their spirits are never fully dampened as they are often assisted by magical allies in their darkest hours.

I know I waxed lyrical about Tolkien’s use of language in The Hobbit, but it deserves a quick nod here as well. He manages to create a real sense of disquiet and ill-omen in his narrative which is as thrilling as it is alarming for the reader. Let’s take for example the Black Riders, faceless, evil beings – formerly the nine Men gifted with Rings but who have faded away under their influence to become Ringwraiths dominated under Sauron’s will. Seated astride ebony black horses, they plague Frodo and company throughout the novel trying to obtain the One Ring. Tolkien portrays them as menacing phantoms always close at hand but not always seen. The feeling of being watched seeps eerily through the chapters; so much so that the reader feels as anxious for the characters to get to somewhere safe as if it were they themselves being constantly chased.

As TFOTR went on I found myself growing fond of every member of the fellowship, but I have to say my favourite character is Legolas the Wood Elf. Not only a moral and brave character who forms an unlikely friendship with Gimli, he also (like all elves) can slay an enemy with a delicate yet ruthless grace. In fact, all his movements are silent, swift and elegant which is always admirable to the average awkward human. One of the most wondrous sections of the book is when the company takes refuge in the dreamlike Elven realm of Lothlórien, ruled over by the Lady Galadriel and her husband Lord Cereborn. Tolkien’s imagination knew no bounds in creating this extraordinary place where each elf captivates the company and the reader with their endless poise and refinement.

Yet alas it is soon after this moment that the fellowship encounters great difficulty and splinters, which is where the novel ends. Luckily, I won’t be left on this cliff hanger for long as volume two, The Two Towers, is already in my possession.

I’m glad to say that TFOTR is an extremely worthy successor to The Hobbit, and I look forward to continuing on with the saga of Middle-earth.

Happy reading,

Imo x