Blog Nº 35

“We’re not colonising the Savages. They’re colonising us.”

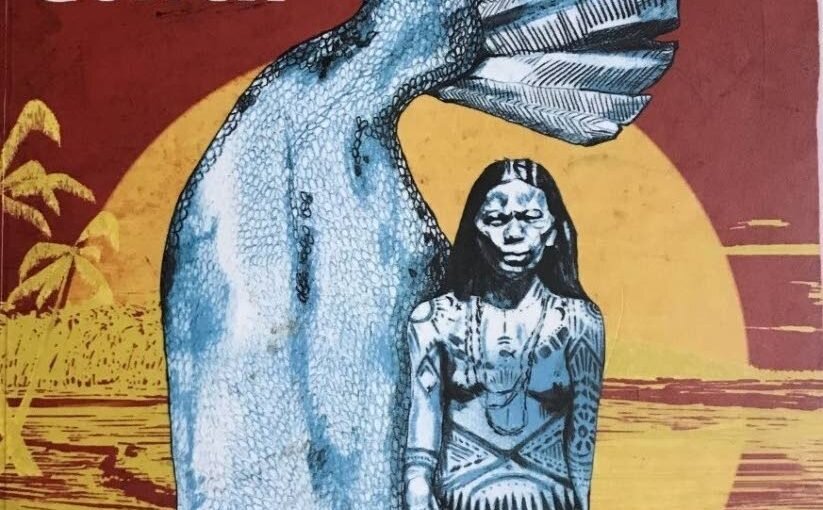

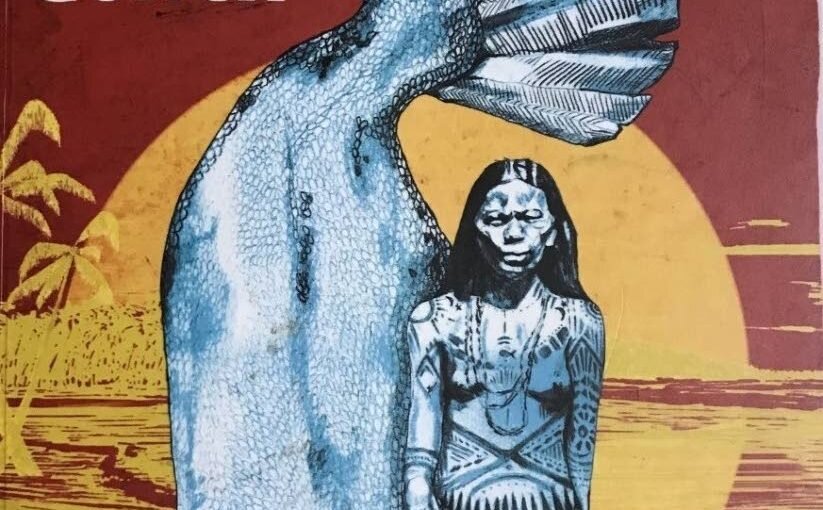

Several critics have called Black Robe an extraordinary novel, and I would have to agree. Moore has created a work that is highly suspenseful and full of physical and spiritual adventure, as well as raising questions of morality, faith and identity.

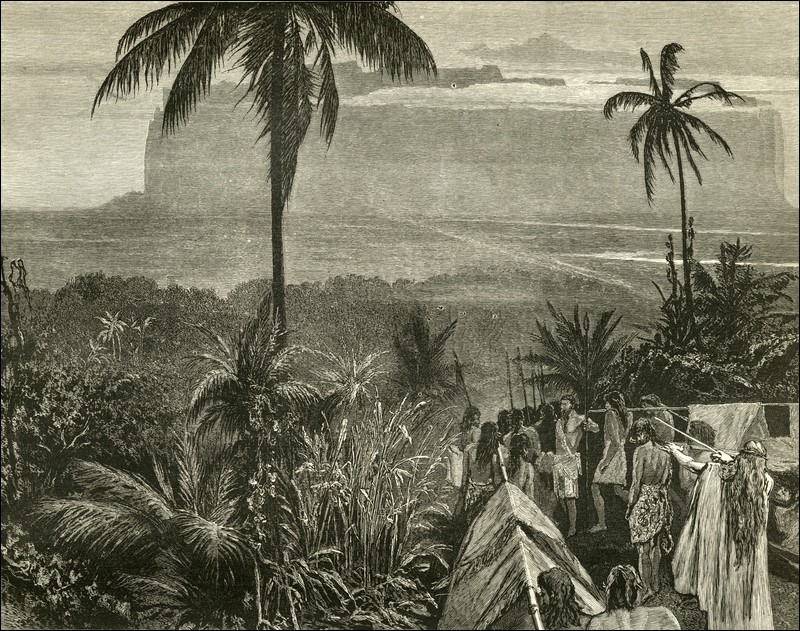

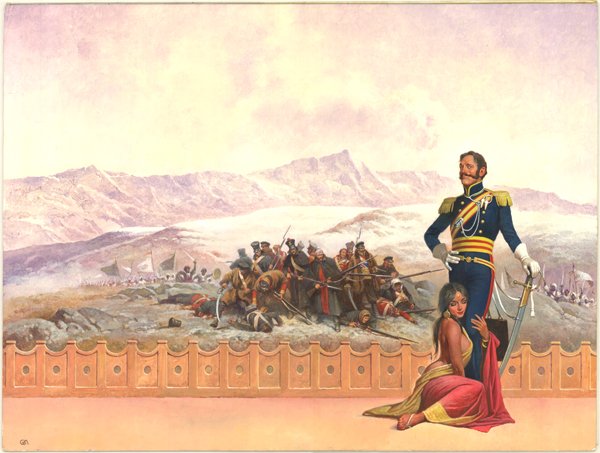

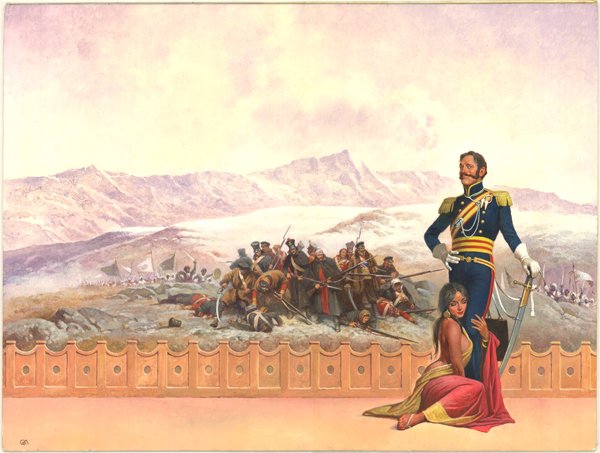

Black Robe is set in seventeenth-century New France, or Canada, shortly after settlement by the French. The central theme of the book is the collision of European and Native American cultures, and we witness this through the story of idealistic Jesuit priest Laforgue. In Quebec, in exchange for muskets from the French, a group of Algonquin agree to take Laforgue and his young assistant Daniel upriver to help them reach a Huron settlement to relieve a priest at the Jesuit mission there. This mission is long and treacherous, and along the way both parties suffer identity crises as they struggle to understand each other’s culture and faith.

(NB: First Nations people historically called Jesuit priests ‘black robes’ due to their religious attire.)

Undoubtedly, Black Robe is a harsh, uncensored and bleak portrayal of life in this era, meaning there are many shocking moments throughout the story. The wilderness that the group travels through is totally unforgiving and Laforgue struggles to navigate it the way the Algonquin do. Furthermore, the native Americans are portrayed as having no filter when it comes to language, humour, sexual relations and more. When members of the group are captured by some hostile Iroquois, we witness some horrifying scenes of torture, cannibalism and sexual harassment. Jesuitism comes across to the reader as a thoroughly miserable experience, full of self-deprecation, fear of God and the inner struggle between human desire and the abstinence required by the religion. We hear in detail about Laforgue’s battle with this, and there are several moments where he succumbs, often by methods as uncomfortable as secretly observing his assistant Daniel and an Algonquin girl having sex, for which he punishes himself afterwards.

The most interesting aspect of this novel is the impact of this early colonialism both on the Native American and French sides. Black Robe demonstrates this mainly through the clash of religions. Whereas the Algonquin believe in the power of nature and the presence of spirits in the world around them, Jesuits belong to Catholicism and believe in the teachings of the christian God and the Bible. Moore said of his book, ‘the only conscious thing I had in mind when writing it was the belief of one religion that the other religion was totally wrong. The only thing they have in common is the view that the other side must be the Devil.’

On the journey, the Algonquin begin to suspect Laforgue is a demon due to his beliefs while Laforgue tries (unsuccessfully) to convert the Algonquin to Christianity because he believes their “heathen” religion will see them end up in Hell. However as the journey wears on, both sides struggle with an identity crisis. Once faithful assistant Daniel renounces his Jesuit faith completely when he falls in love with Annuka, an Algonquin girl. She also struggles to understand why with him she wants to be monogamous because her tribe has always been more free when it comes to sexual relations. Other Algonquin start to realise with dismay that since the French arrived, materialism and desire for ‘things’ has seeped into their culture when it wasn’t there before. Laforgue, who set out on this mission full of idealism and a passion to convert as many as possible, is really struggling with disillusionment by the time he eventually reaches the Huron settlement which is rife with fever and death. Black Robe culminates in one of the most powerful, thought-provoking final chapters I have ever read, which lays bare the confusion and desperation of both the Hurons and Laforgue caused by an unprecedented clash of culture, faith and moral direction.

Though not for the faint-hearted, I would highly recommend Black Robe because it looks at a pivotal moment in history and does not hold back in its portrayal of the complexities of a collision of worlds.

Happy reading,

Imo x