Blog Nº 62

“All was false. It was known to be false, but everyone lied about the lies, until no one knew where the lies began and ended.”

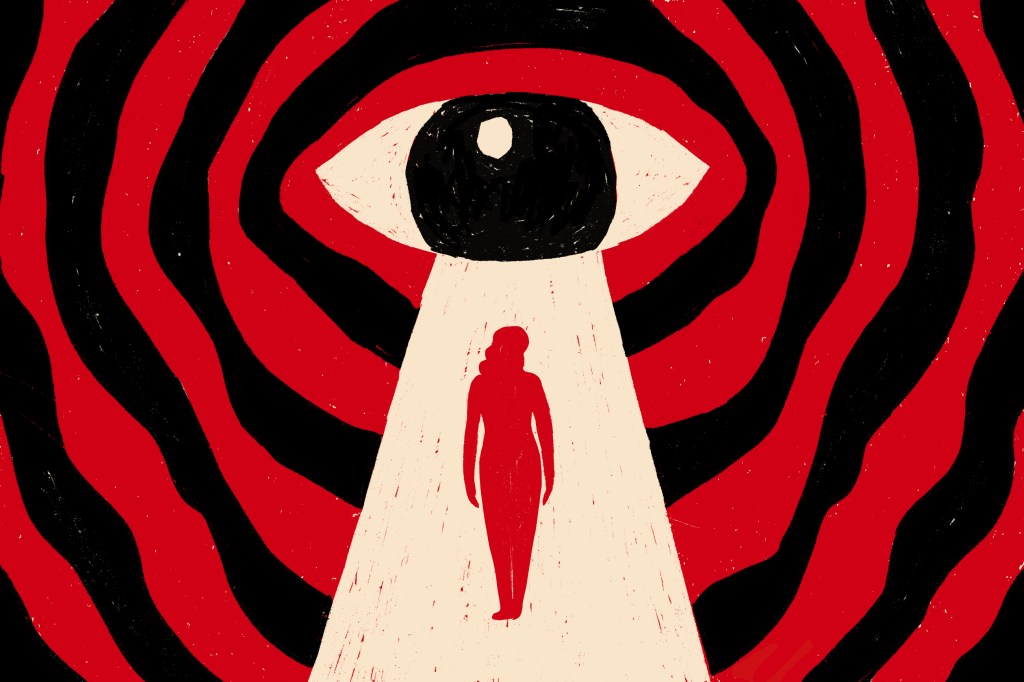

It is a brave thing to take on a re-telling of one of the most well-known British novels of all time, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, particularly in so bold a manner as Newman does so. In this story, the object of Winston Smith’s gaze looks back, reclaiming agency to tell her own tale which will both shock and captivate readers.

Newman has faithfully recreated Orwell’s vision of the future by carefully considering the language and culture of the original novel as well as guiding us through familiar landscapes such as the bleak, dingy factory floor of the Ministry of Truth. Many of the plot points we encounter are familiar to us, though inverted to be from Julia’s perspective. But Newman is able to move beyond the two-dimensional Julia that is portrayed by Orwell. Even by having her clock out of her factory shift due to ‘sickness: menstrual’, the reader is treated to a look at how women fared under the totalitarian regime and how their experience was entirely different to that of men. Seeing Julia at her dormitory hostel, how she interacts with other women there and how surveillance plus a lack of privacy and autonomy weigh differently on them is a compelling new element to this Orwellian existence.

We learn that sexuality is a key part of Julia’s character and how despite being shaped by abuse, voyeurism and other factors, she still seeks and enjoys pleasure where she can. The focus on how sex and relationships work in an oppressive, surveilled world add nuance to what occurs between her and Winston but also between her and several other characters in the novel. Pregnancy and motherhood (both regime approved and not approved) are also put under the microscope, further providing insight of the uniquely female struggles faced in the Britain (or ‘Airstrip One’) of Nineteen Eighty-Four. Newman also paints a vivid picture of Julia’s childhood which makes her grit and determination to survive, her ‘cheerfully cynical’ nature and how she has so far made it through life under oppression highly convincing.

The reader continues to be surprised by the twists and turns in the novel, including insight into previously unexplored characters such as O’Brien of the Thought Police, though eventually we arrive at the tragic ending readers of Nineteen Eighty-Four will know all too well. While the torture that occurs in the Ministry of Love and Room 101 aren’t portrayed quite as horrifically and convincingly as in the original, Julia still manages to lay bare the life-altering cruelty that takes place there.

In Orwell’s novel, no crack in the totalitarian regime is allowed to show at the end. It concludes with no hope at all, with resistance resigned to be a futile expression of false hope. Newman wants to give the reader a dramatic conclusion to Julia’s personal narrative as well, meaning that in this story we get a glimpse into what happens after Orwell’s ending. Some may argue that there is less power in this, but I disagree. While I can’t reveal what happens, Newman absolutely honours the message that Orwell was initially trying to get across, leaving readers feeling equally as uneasy. The only difference is that while it was difficult to remain hopeful for Winston, readers here will be a little more convinced that Julia will endure and survive.

Happy reading,

Imo x