Blog Nº 29

“The sea, that expanse of nothingness, could reflect a man back on himself. It had that effect. It was so endless and it moved around underneath the boat. It wasn’t the same thing at all as being on any expanse of earth. The sea shifted. The sea could swallow the boat whole. The sea was the giant woman of the planet, fluid and contrary. All the men shuddered as they gazed at her surface.”

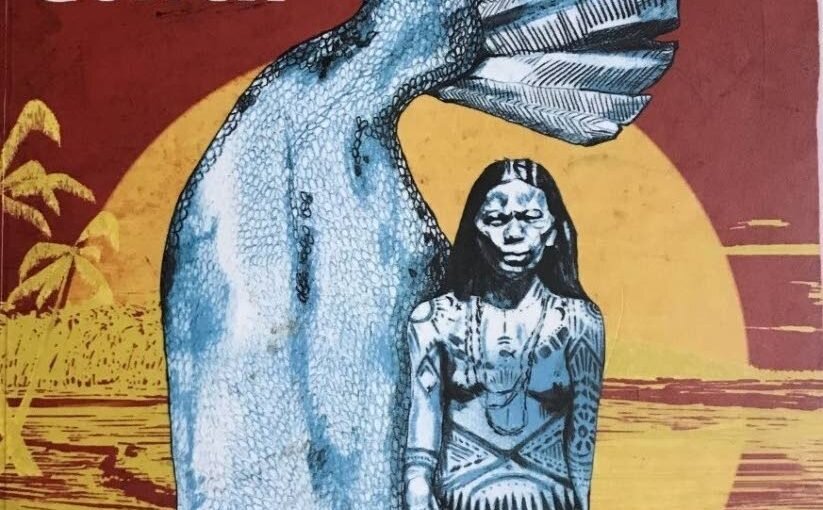

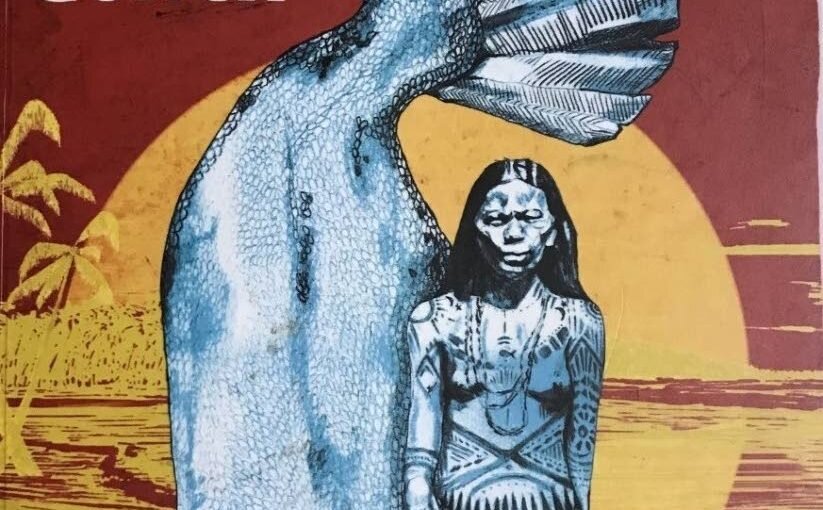

I have always enjoyed stories that contain elements of myth and legend, but this is the first time I have delved into the world of Caribbean folklore. The Mermaid of Black Conch is arresting and powerful while unravelling all pre-conceived notions of what a mermaid is. It gives an insight into the long and fascinating history of the Caribbean through the unique story of Aycayia, the girl cursed to be a mermaid for all eternity.

The story begins in 1976 in the small town of St Constance, located on the island of Black Conch in the Lesser Antilles. An unsuspecting young fisherman, David Baptiste, is out in his pirogue boat singing and playing the guitar whilst waiting for a catch. What he doesn’t expect to attract is the mermaid Aycayia, a beautiful young woman cursed long ago by jealous wives who has been swimming in the Caribbean Sea ever since. So entranced by his music, when Aycayia hears David’s boat engine again she follows it, only to find herself a target for American tourists visiting the island for its annual fishing competition. Dragged out of the sea by the Americans and strung up on the dock like a trophy, Aycayia believes her fate is sealed. However, when night falls it is David who rescues her and takes her home. Slowly, Aycayia begins to transform back into a woman, much to the joy of David who has become completely enamoured with her. Unfortunately, transformations are not always permanent, especially when centuries-old jealousy is at play. Even the love between Aycayia and David may not be enough to break the curse.

Author Monique Roffey has succeeded in producing a spellbindingly rhythmic narrative often through simple literary devices such as repetition. For example, “she was floating port side of his boat, cool cool, like a regular woman on a raft, except there was no raft”, “I am an ol’ man now, and sick sick so I cyan move much”, or “after the fish-rain I realise curse strong strong.” She uses this technique frequently throughout the novel, indicating that it has been inspired by folkloric tales passed down for centuries through nothing but spoken word, made memorable by repetition. The fact that all dialogue is spelled phonetically – “Dou dou. Come. Mami wata! Come. Come, nuh” – only adds to the significance that spoken word has in stories like this. Roffey continues to show how important different voices are in The Mermaid of Black Conch by having several narrators sharing the storytelling duties. We hear from David through his retrospective diary entries in 2016, an unknown narrator present in 1976 who tells us the words and actions of all characters, and Aycayia herself who speaks in verse, which further emphasises the memorable quality of the narrative and her difference from the other characters. Furthermore, Aycayia always speaks in the present tense, yet it is clear she is looking back on events, suggesting that being stuck in an everlasting curse has made all notion of time and tense completely meaningless. This fusion of unique voices and narrative styles makes for a highly enchanting read.

It’s also important to focus on Aycayia herself. She in no way conforms to the trope of a siren sitting atop a rock, combing her hair and luring men to their deaths with her beauty. In fact, Aycayia is distinctly ‘unbeautiful’ when compared to Disney-esque mermaids. She has matted dreadlocks which are full of sea creatures who have made a home there, her teeth are sharp and pointed, she has dorsal fins on her back, she smells of salt and fish, she has webbed hands, and her tail is enourmous and scaly. Personally, I think she is a more authentic mermaid because she is at one with the sea, and is striking in a magical, sharp kind of way. Significantly, she has no idea how to lure in a man because she was cursed to this fishlike form when she was just on the brink of womanhood. It transpires that she used to dance for the men of her village centuries ago, not realising in her innocence why the men enjoyed it so much. Consumed by jealousy, the wives of these men chose to make her a mermaid when cursing her because they knew her tail would bind her ‘sex’, making her unable to seduce a man let alone sleep with one. It is not until she is on land, tailless and human, that she is able to finally ‘become a woman’ and understand what it is to physically love a man, a joy that she finds with David. Even though the long-dead wives can still wield their power over Aycayia, it is satisfying to know that whatever her fate, she has bested them through her relationship with David and this can never be taken away from her, despite the eternal cruelty of these scorned women.

I have read several books featuring mermaids, but I have to say that The Mermaid of Black Conch is now my standout favourite. It encompasses myth and legend, love and the cruelty of human nature as well as the beauty of the Caribbean and its complex history. I highly recommend this captivating and unique novel.

Happy reading,

Imo x