Blog Nº 25

“The most extraordinary articles of domestic life are looked on with some interest, if they are brought to light after being long buried; and we feel a natural curiosity to know what was done and said by our forefathers, even though it may be nothing wiser or better than what we are daily doing or saying ourselves. Some of this generation may be little aware how many conveniences, now considered to be necessaries and matters of course, were unknown to their grandfathers and grandmothers.”

James Edward Austen-Leigh, ‘A Memoir of Jane Austen’ (1869)

It is already a well-established fact that I adore the British Regency period (1789-1830). To me it is the most interesting, colourful and important time in our country’s history. I dedicated much of the history side of my French & History degree to studying the period and also pursue this interest in my own time. If I could, I would use one of my three wishes to travel back in time to experience it for myself. Fortunately, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Regency Britain really is like stepping back in time. Mortimer calls it ‘A Handbook for Visitors to the Years 1789-1830’ on the opening page and it certainly lives up to this description. I am a social and cultural historian at heart, so it was brilliant to read a book solely dedicated to portraying this era as a lived experience rather than something to be studied. We find out what people wore, ate and drank, how they travelled, what they were thinking, believed in and were afraid of, what their world looked, sounded and felt like and much more. This book is an eye-opening, exciting and involving trip back in time.

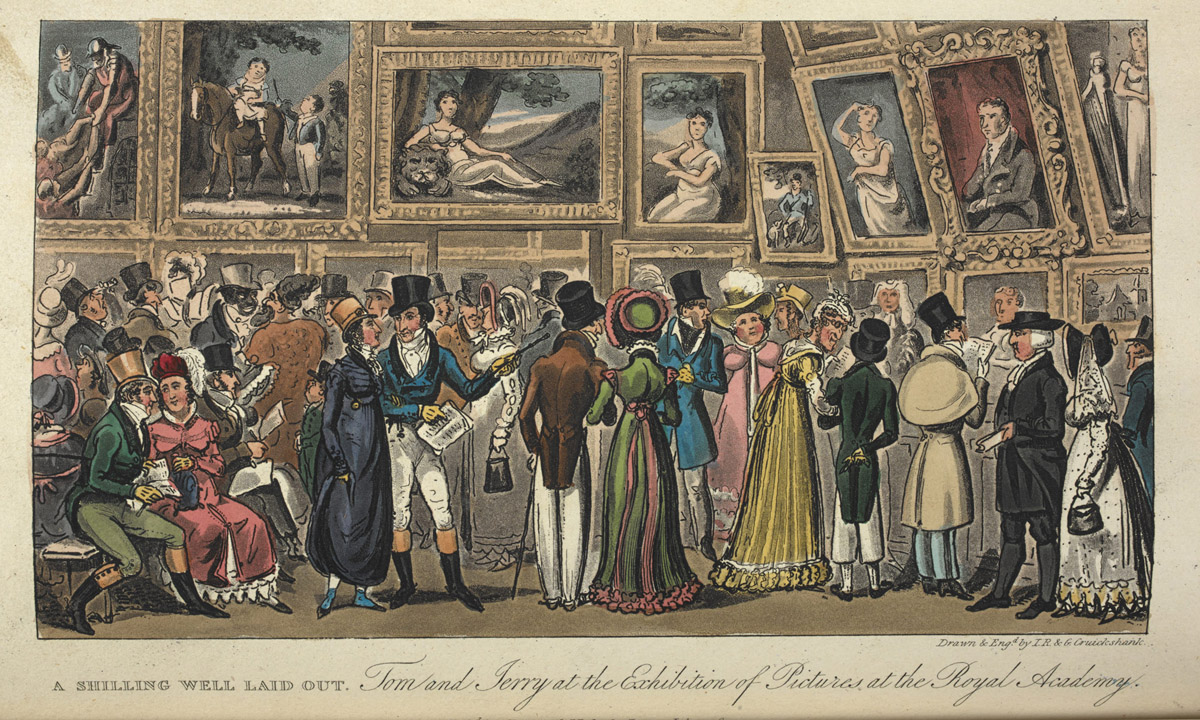

Mortimer certainly covers all bases in The Time Traveller’s Guide to Regency Britain. The book is divided into the following sections: The Landscape; London; The People; Character; Practicalities; What to Wear; Travelling; Where to Stay; What to Eat, Drink & Smoke; Cleanliness, Health & Medicine, Law and Order; Entertainment. It also contains two glossy sections featuring paintings, illustrations, caricatures and prints from the time which really add to the feeling of visiting the Regency period. It would be impossible to discuss all the chapters in this blog, so I have selected a few personal highlights. Fundamentally though, this is an era where big things are happening all at once in the form of unprecedented social, political and economic change. It was the last time that Britons truly lived in a period of unchecked extravagance, fun, mischief and thrills before the stiff curtain of Victorian morality descended. The Regency is the age of Jane Austen and the Romantic poets, the art of John Constable, the trendsetting stylishness of Beau Brummel and the premiere of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. At the same time, Britain is celebrating military triumphs at Waterloo and dealing with the menacing threat of revolutions and tragedies like the Peterloo massacre. Never has there been a time of such wild contradiction in British history.

Something charming about this book is Mortimer’s analysis of everyday concerns that are so banal you would never have thought to consider them when looking back at the past. Take, for example, the weather. As Mortimer points out very astutely, when delving into history it is easy to forget about the small but fascinating details when you are wrapped up in the big picture. It is heart-warming to know that Regency folk talked about the weather just as much as we do in the modern day, making it truly a subject that unites people in their Britishness. Something else you might not have considered is the time, given that time is standardised in the modern world. Though Regency people had perfectly functioning pendulum clocks, the actual hours in the day were heavily localised. Therefore, what might be 10:0am in London could be 10:20 in Leeds, meaning that scheduled meet ups were not always straightforward and travellers between towns would be in the habit of adjusting their watches accordingly on arrival with the town’s public clock. These are just a couple of points discussed in the ‘Practicalities’ chapter, and I think these sorts of topics are just as worthy of study as the big stories in history because they really shine a light on how people truly lived and what they experienced day-to-day.

In my degree I really enjoyed studying all things Regency: the Empire, the fashion, the royals, the rise of consumer culture, society norms, the Romantics and literature, the art, the humour, the architecture, social change, the politics and more. Therefore, it was great to see Mortimer bring these subjects to life in The Time Traveller’s Guide to Regency Britain. However, as you might have presumed, what I really enjoyed was finding out things I didn’t already know about the Regency period. For example, I found it interesting to learn just how blurry the boundaries between sexual morality and immorality were in this era, what attitudes were towards homosexuality and transvestitism, or how superstitious or cruel and compassionate people were, both in terms of other people and animals. People were still horrified by cruelties during this period but what was considered cruel differed greatly and again, there were contradictions. On the one hand, harsh punishment of felons and public hangings were still major entertainment for the public while on the other hand opposition to death penalty was growing and prison reforms were happening. It is interesting that at the same time, people (especially men) were much more expressive of their sensitivity. Though you can often find gentlemen duelling for their honour, there is no such thing as the strong silent type. Men are much more emotional – judges could cry in court when delivering a verdict and when MP Samuel Whitbread commits suicide in 1815, many members of the House of Commons who rise to pay their respects cannot hold back their tears. It is the original instance of there being ‘not a dry eye in the House.’

Aside from learning about the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution in the Regency and reading Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1831), I confess that I was not aware of how exciting this era was in terms of scientific developments. Frankenstein is of course based on the theory circulating at the time that electricity could bring people to life after Luigi Galvani’s famous experiment in which he stimulates the legs of dead frogs. Again, as electricity is the norm today, it is easy to forget how much it amazed Regency people. It was the first time that objects could be moved without touching them or that things could be lit up without a match, making it a mysterious and fantastical revelation. Electricity along with other developments such as the discovery of new planets, the phrases ‘chemistry’, ‘biology’ and ‘geology’ taking on greater meaning, the invention of the first steam locomotive and hot air balloons, and the exhibition of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s ‘heliographs’ (early photographs) in London, gave people a startling glimpse into the future. Suddenly, everything seemed possible and people imagined a future of endless innovation, which of course is now our past. I’m almost jealous that I have grown up taking these things for granted – I’m not sure that there’ll be an age of discovery quite like this ever again.

These are just a few examples from a book brimming with fascinating insights into how people thought and lived during the Regency period. I applaud Ian Mortimer on such a well-researched, original look into Britain’s most fascinating era. His captivating writing style and far-reaching chapter base really does make for an incredible trip back to the past. With The Time Traveller’s Guide to Regency Britain in hand I would feel more than confident navigating my way around this period and making the most of it. Regency people played an integral role in shaping who we are today in so many more ways than we realise, and this book is a triumph in showing us how. I really recommend this book to anyone looking to understand who we are and where our modern selves came from.

Happy reading,

Imo x