Blog Nº 7

“Humbling women seems to me a chief pastime of poets. As if there can be no story unless we crawl and creep”

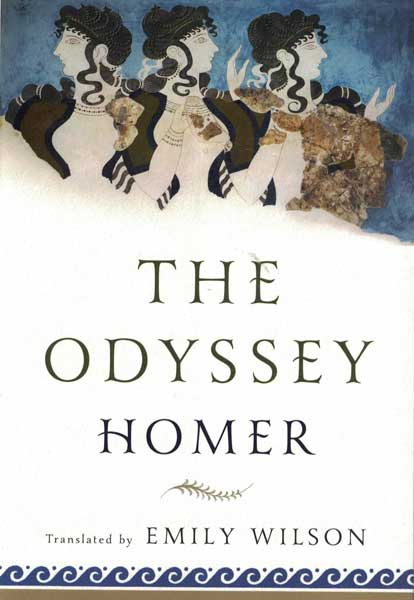

DISCLAIMER: please read my blog on The Odyssey before reading this one 🙂

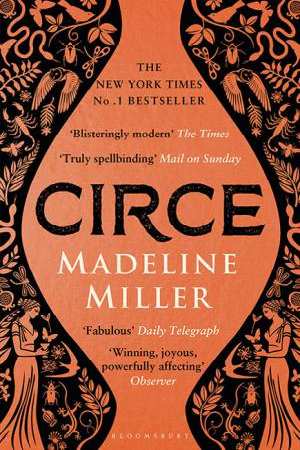

Alongside Emily Wilson, Madeline Miller is another female author who must be praised for her sensationally modern twist on Homer’s The Odyssey. Her novel centres on the life of nymph and sorceress Circe, who is dealt with in but a few lines in Homer’s work.

From the start, it is clear that despite being a goddess, Circe’s life is not luxurious and languorous. Nymphs are the lowest of the gods and their function is fundamentally to be married off to strengthen the power of their family; ‘in our language, it [nymph] means not just goddess but bride’. She is deemed unattractive, uninspiring and just downright strange by her father Helios and her mother Perse, so they are cruel to her and pretty much completely dismiss her. A dalliance with a mortal fisherman, Glaucos, sets Circe’s story in motion. Her efforts to turn him into a god despite not having the divine powers of her father reveal that she is a witch; she successfully uses pharmaka (sorcery) for the first time to change him. With his newfound powers, Glaucos scorns her without a second glance in favour of beautiful sea nymph Scylla. In a fit of jealousy and hurt, Circe uses pharmaka once more to turn Scylla into a hideous sea monster (that Odysseus will later encounter), and it is for this that she is banished to the island of Aiaia for all eternity. And yet, the story does not end here; this is where it begins. Miller has brought Circe to life as the woman who will not be silenced or caged as Zeus and her father desire.

Sadly, as Homer passes over Odysseus’ encounter with Circe so briefly, there is little even Emily Wilson could do to give her character more depth. In The Odyssey, she is simply an unpredictable, lonely witch who turns all men that come to her island into swine and of course, Odysseus is the one who can seduce her and keep his crew from this fate. Miller has given their relationship the airtime it deserves, as Odysseus stays on Aiaia for months (despite being ‘desperate’ to return home to his wife and son). I enjoyed the fact that in Miller’s modern re-telling, unsurprisingly Odysseus is not the be all and end all of charm and seduction. Circe has several lovers over the course of the novel, and each time it is her choice, and often by her own initiation. Furthermore, we learn that her tradition so to speak of turning men to pigs is a defence mechanism after she was once brutally raped by the captain of a passing crew. In the patriarchal (and dare I say misogynistic) society of Ancient Greece, it is likely that the concept of rape did not exist in the eyes of most men; Circe’s experience starkly demonstrates its everyday occurrence.

Aside from her relationship with Odysseus, Miller shows us how Circe plays a role in many famed Greek myths, so if you want a round trip of the greats, this book is for you. For example, as a child she was the only one in her father’s court to show kindness to Prometheus during his first round of punishment. When her sister Pasiphae spawns the minotaur, it is down to Circe to create a spell to temper it while Daedalus builds the labyrinth to imprison it in. Indeed, her role in Scylla-gate (which has many versions) led to the creation of one of the most legendary monsters in Greek myth. An invisible player she may sometimes be, but she is undoubtedly a very important one. Bringing her to life as Miller has done as ‘the good witch’ is revolutionary in the sense that it starts eroding the idea that all the greats of Greek myth are male.

On a technical level, I was extremely impressed by the language of the novel. Evocations of antiquity through Miller’s tone, vocabulary and writing style are faultless; I felt like I was reading a text written in the same year as The Odyssey despite its unwaveringly modern take on Circe’s story. The level of detail and knowledge weaved seamlessly into the story (as if it was created on Daedalus’ loom no less) is a credit to Miller and her research.

Circe is a story that will dazzle your imagination with the big guns of Greek mythology and the world of the Ancient Greek Empire. This is reason enough to give it a read, but it is Circe herself that will leave the most enduring impression upon you. Her trials and tribulations are somehow both ancient and modern, relatable and godlike, optimistic and harrowing; they undeniably show that yes, she does matter, no, she will not be kept down and that yes, she is more than what she was designated to be by men such as Homer and Ovid.

Happy reading,

Imo x