Blog Nº 9

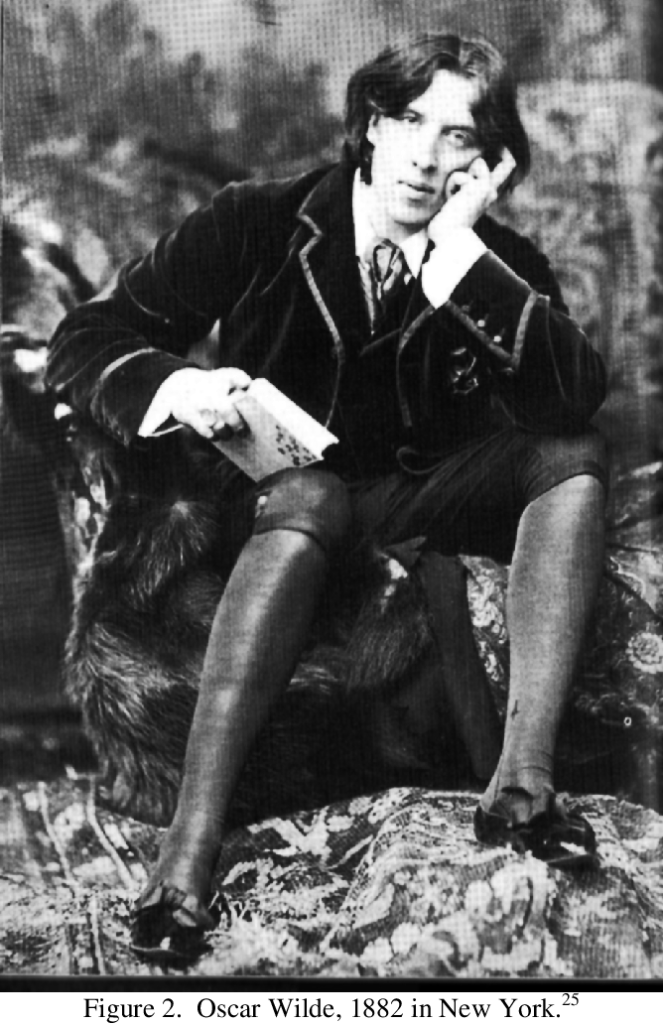

“The horror, whatever it was, had not yet entirely spoiled that marvellous beauty”

There is and always will be a soft spot in my heart for Oscar Wilde, certainly one of the most provocative literary figures of the nineteenth century. After going to a production of the brilliantThe Importance of Being Earnest (blog coming soon) with my mum some years ago, I became infatuated and have since read all his short stories, plays, essays and this, his only novel. He was even the subject of my 5000-word Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) undertaken alongside my A-Levels, in which I tasked myself with the question, ‘to what extent was the Victorian press responsible for Oscar Wilde’s celebrity?’ Research for this took me to the National Archives, where I felt privileged to read his handwritten letters from his time in prison. Humbly then, I consider myself to be the epitome of the Wildean ‘fangirl’ if such a thing exists.

As part of my EPQ I examined the blatant homoeroticism running through The Picture of Dorian Gray, as it was used as evidence against Wilde in his sensationalised trial for ‘gross indecency with other men’ in 1895, a proceeding which certainly elevated his celebrity. Therefore, I am going to use this blog to discuss other key themes in the text such as Gothicism and aestheticism.

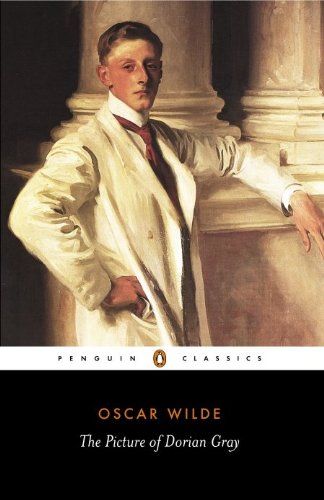

This novel is an ill-fated tale of moral decline and philosophic instruction for our unfortunate protagonist, the young aristocrat Dorian Gray. Basil Hallward, Dorian’s close friend and a professional artist, paints a portrait of Dorian because he is completely infatuated by his youth and extraordinary beauty. At first Dorian is delighted with the painting; it only dawns on him that his beauty – so perfectly preserved on the canvas – will fade with age after Basil’s amoral friend, Lord Henry Wotton, informs him of the fact. So enamoured with his own radiant portrait, Dorian exchanges his soul for eternal youth and beauty in an exquisitely Faustian twist. As a result, he is drawn into a corrupt and sinful double life, indulging unspeakable desires in secret while maintaining a gentlemanly façade to polite society. Only the painting bears evidence of his decadence while he himself retains his youthful innocence and beauty.

The lurking presence of the painting that becomes harder and harder for Dorian to ignore is one of my favourite gothic elements in the novel. The physical embodiment of his deal with the devil, the painting becomes more and more hideous each time Dorian does something terrible; as well as ageing repulsively, there is a chilling cruelty in the eyes and mouth of the painted Dorian that grows increasingly and unnervingly noticeable as the novel progresses. Locked away in a dark dusty room high up in the house, the strange horror of the painting is alike to a nightmare you can’t quite shake off.

And yet, Dorian is not too concerned with the degradation of the painting at first. He is too busy engaging in debauched delights; think opium dens and licentious behaviour in the darkest corners of London.

It is only when his manner and behaviour become too cruel for him to ignore – because indeed the soul can decay in more ways than one – that the painting and what he has done begins to weigh down upon him. In this way, the painting is a motif for an inverted magic mirror. It allows him to live for hedonistic pleasure for a time, but always reflects the ugly truth of his crimes back to him no matter how much he wishes it not to.

I find this very interesting in the context of Wilde’s ‘art for art’s sake’ aesthetic philosophy. Scathingly received by critics at the time for its homoeroticism and allusions to sins that were surely offensive to stiff Victorian moralities, Wilde fiercely defended The Picture of Dorian Gray. In a now infamous aphoristic preface to the non-censored 1891 edition, Wilde vigorously defends art for art’s sake. It is ironic that, although he was referring to the art of his writing, the idea of art for art’s sake is completely vilified in this story. That is, it turns out that the ‘work of art’ that is Dorian should have stayed on the canvas. His pursuit of eternal youth and beauty is his ruination, and it hurts many characters along the way. Wilde’s moral lesson here is that being good trumps looking good; a virtuous soul brings more happiness than beauty, which should only ever be ephemeral.

Dark though this tale is, I must laud its moments of comic relief, provided by Lord Henry ‘Harry’ Wotton. You cannot help but like this gentlemanly rogue despite his amorality due to the Wildean wit bestowed upon him. Many of Wilde’s most famous epigrams come from The Picture of Dorian Gray. An epigram is a phrase that expresses an idea in an interesting, clever, and surprisingly satirical way. Wilde always says the exact opposite of what you are expecting him to say. For example, Harry is of the opinion that ‘it is only shallow people who do not care about appearances’ which is decidedly not how that phrase is usually said. Wilde’s epigrams also turn out to be well-observed and pretty much true, such as in another golden example from Harry; ‘“It is perfectly monstrous”, he said, at last, “the way people go about nowadays saying things against one behind one’s back that are absolutely and entirely true”’. Harry’s enduring friendship with Dorian means that fortunately, readers are exposed to many a memorable epigram over the thirteen chapters.

So then, The Picture of Dorian Gray is a must-read Victorian novel, not only for its thought-provoking themes and intelligent narrative, but for its distinctly Wildean touch. An interesting question to ask yourself when reading it is, who is really to blame for the outcome of the novel? Is it Basil for painting the picture? Is it Harry for targeting Dorian with his bad influence and amoral philosophies? Or is it Dorian himself for enacting his fateful deal? It’s a moral conundrum but I’ll leave that for you to decide…

Happy reading,

Imo x