Blog Nº 39

“Caring too much for objects can destroy you. Only—if you care for a thing enough, it takes on a life of its own, doesn’t it? And isn’t the whole point of things—beautiful things—that they connect you to some larger beauty?”

I have now finished Donna Tartt’s trifecta of outstanding novels. For me, none can beat The Secret History, but The Goldfinch is still worthy of its reputation as an outstanding novel and a modern epic. It is an emotional and melancholy look into just how murky life can become after experiencing tragedy, trauma and neglect.

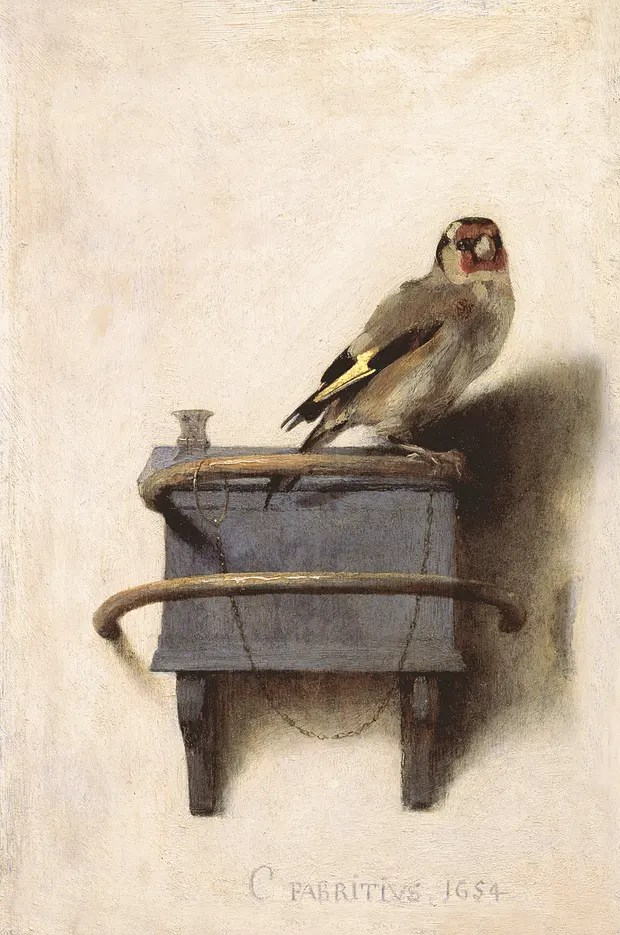

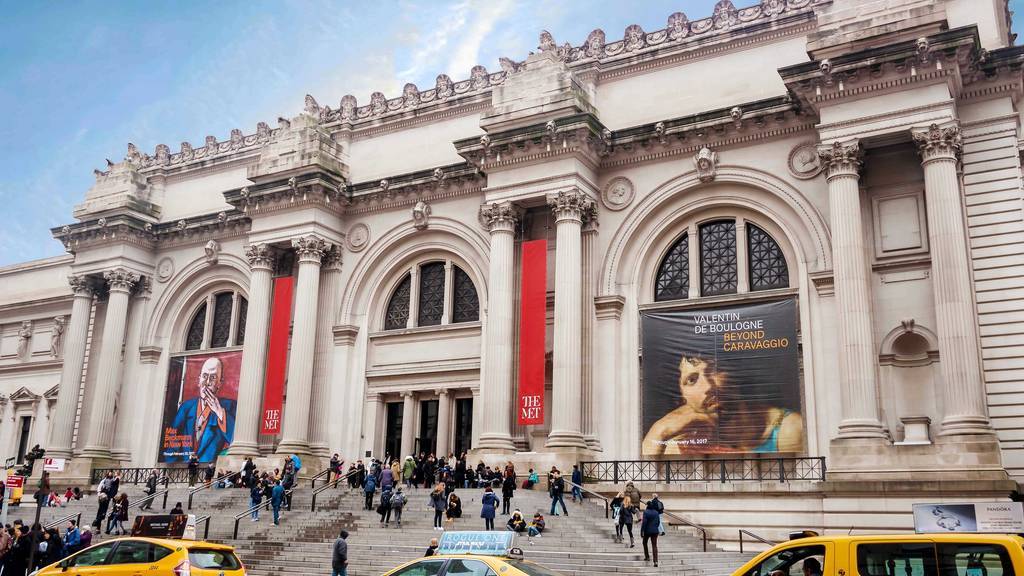

The Goldfinch opens in New York City on thirteen-year-old Theodore Decker, the son of a devoted mother and an absent father. One unfortunate day, Theo’s life is ripped apart when his mother is killed in a terrorist explosion while they are visiting Metropolitan Museum of Art together. Utterly alone and longing for his mother, he is taken in by the family of a wealthy friend, before being shipped off to Las Vegas to live with his father and his girlfriend. Traumatised by the loss of his mother, he holds dear something that reminds him of her, their favourite painting from the Met, The Goldfinch. Known only to Theo is that he has the original 1654 painting by Dutch artist Fabritius in his possession, which he took from the gallery in the wake of the explosion. Faced with neglect and indifference in Las Vegas, Theo finds solace in his friend Boris and in their descent into drugs and alcohol. Ultimately, in adulthood the painting draws him back to New York to revive old acquaintances and slowly drives him into the criminal underworld.

For me, one of the most poignant sections of The Goldfinch is Theo’s time as a young teenager in a Las Vegas suburb. Comprising of soulless new-build homes cut off from the city, most of which are empty or crumbling and some of which have even reclaimed by the Nevada desert, it feels like a metaphor for the failed American Dream. This becomes even more evident when we witness how neither Theo nor Boris have anyone in the world who cares about them, despite the fact that they both live with a parent. They often go hungry because nobody thinks to feed them and they resort to stealing. Theo’s situation at home improves only when his father’s gambling habits are going well. Both affected by trauma and with nothing to do and nobody to wonder about them, Theo and Boris are in and out of school, and spend their evenings getting drunk and high on whatever drug they can find. It is quite shocking to read about such young teenagers drinking until they’re sick or taking acid with no parental awareness or care for what they’re doing. Theo narrates this portion of his life in such a lucid and resigned way that it feels like he has accepted the fact that one tragic incident knocked him into a different life, one that is consumed by loneliness, substance abuse and monotony.

Like Tartt’s other two novels, the research and attention to detail are remarkable. The Goldfinch allows a rare glimpse into the world of art and antiques, and the murky underworld that accompanies them. As an adult Theo has learnt the antiques trade, including how to restore pieces falling to ruin. He works in New York with Hobie, the business partner of a man who spent his last minutes with Theo in the aftermath of the explosion. Every choice and every relationship Theo has comes back to the incident and the taking of the Goldfinch painting. Twists and turns, his continued reliance on drugs and his guardianship of the painting eventually brings him back in touch with old friends from the city and Boris, and reluctantly pulls him into the greedy world of criminal art fraud and theft which leads to a page-turning bid for escape. The Goldfinch has many elements of a Shakespearean tragedy set against a modern and truly American backdrop.

Overall, The Goldfinch is an extraordinary novel that opens up a world that most of us know little about. Through watching Theo’s life and how young he experiences darker elements of adulthood, it is hard not to think that he is just a boy trying to muddle through after the devastating loss of his mother.

Happy reading,

Imo x