Blog Nº 13

“Dear Scarlett! You aren’t helpless. Anyone as selfish and determined as you are is never helpless. God help the Yankees if they should get you.” – Rhett Butler

Introduction

Without a doubt, Gone with the Wind (GWTW) has earned its place firmly within my top five novels of all time. I can see why it took Margaret Mitchell ten years to write it, because it truly is a masterpiece of literature and joins other heavyweights on the roster of Great American Novels. Hopefully after reading this blog, you will want to lose yourself in the US Civil War era and gorge on this story of love, loss, war, survival, coming of age and so much more.

Disclaimer: there was a lot to say so this is an essay-length blog (sorry!)

Structure & Background

GWTW is the crème de la crème of epic novels, structured into five parts spanning the twelve years between 1861 and 1873. In other words, the novel opens on the eve of the American Civil War (1861-1865) and ends during the post-war Reconstruction era (1863-1877). This is a time period that I have studied in some depth and I find it fascinating. In fact, GWTW has become a crucial reference point for any historian researching this era.

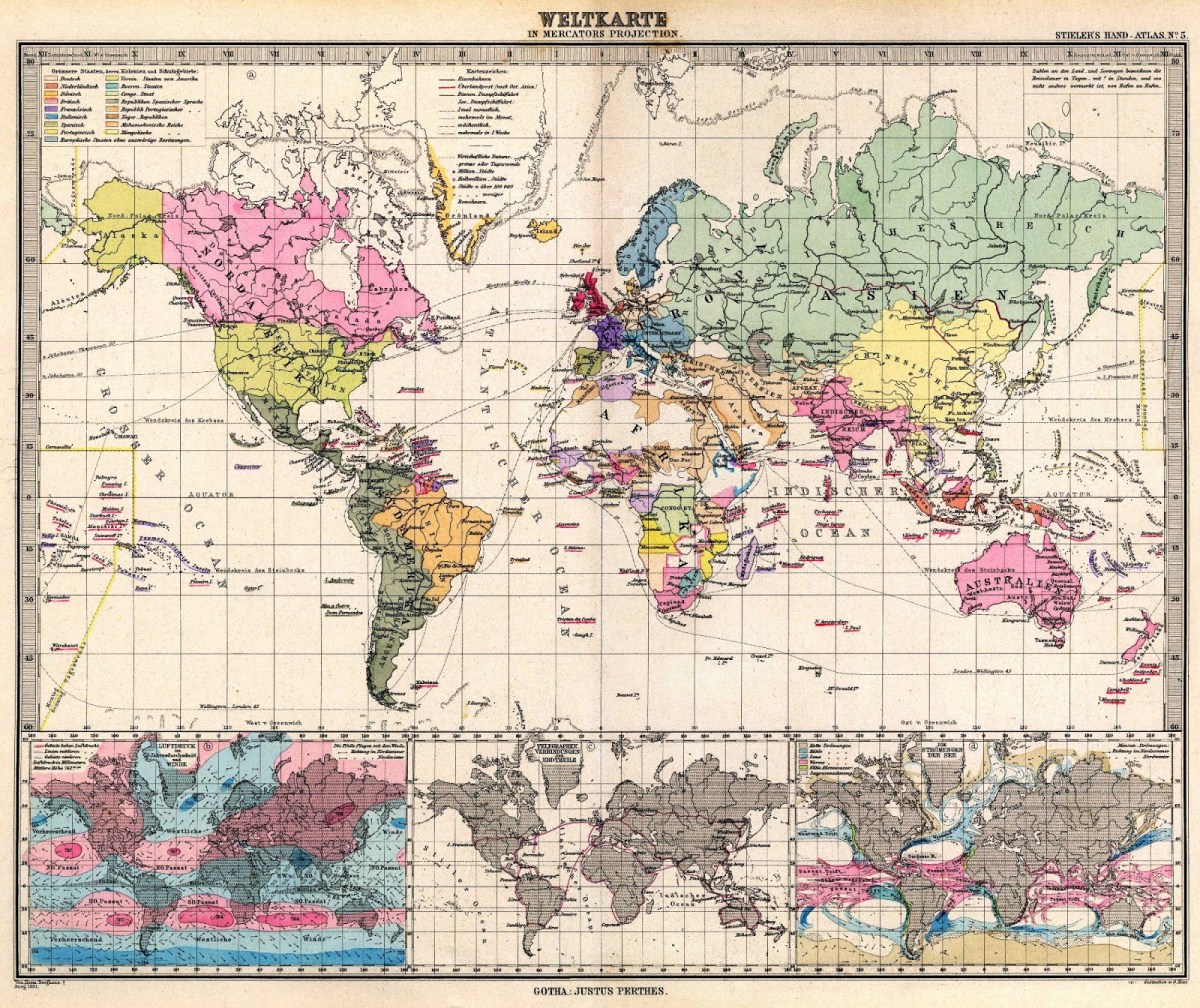

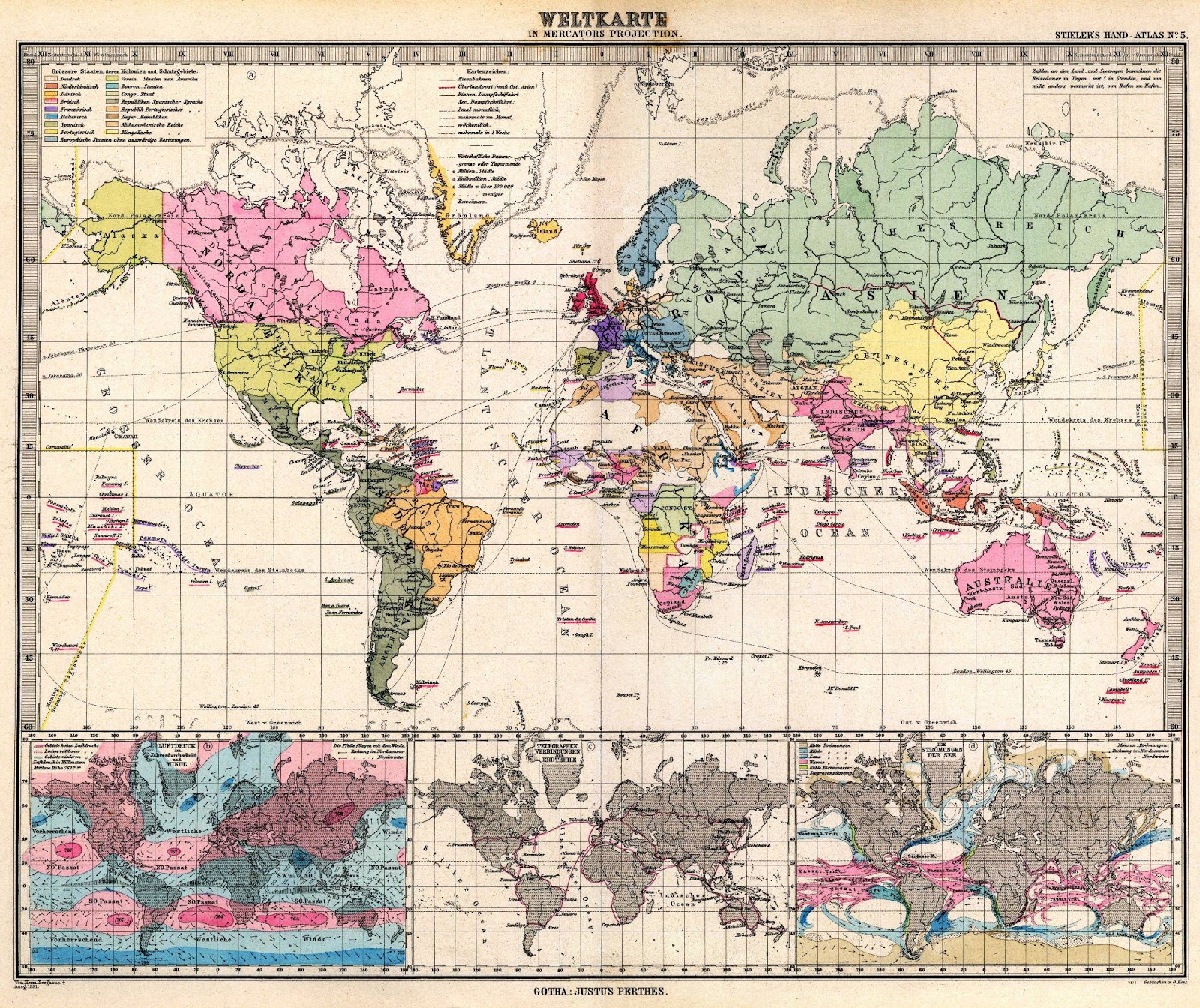

The novel follows the life of protagonist Scarlett O’Hara, a typical southern belle, through these turbulent times. The daughter of a rich planter, Scarlett’s home and one of the two main settings of the novel is the family cotton plantation, Tara, located in Clayton County, Georgia. Mitchell evokes a vivid and romantic vision of the Southern plantation lifestyle with her vibrant descriptive passages of Tara. The other key setting, and where Scarlett mostly resides after the war has begun is Atlanta, Georgia, which at that time was the up-and-coming city of the Deep South.

Fundamentally, at the novel’s opening, Scarlett is a rather superficial 16-year-old whose only real concerns are maintaining her eighteen-inch waist, stealing the beaux of her friends for fun, and trying to ensnare the one man she thinks she loves, Ashley Wilkes. Scarlett could not care less when, two weeks into the war, her first husband Charles is killed in battle. This marks a crucial turning point in the novel as it is when Melanie Wilkes, the sister of Charles and wife of Ashley, invites Scarlett to come and stay with her and her Aunt Pittypat in Atlanta.

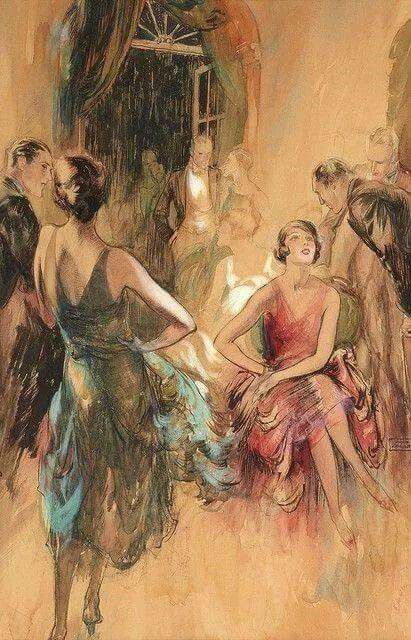

Though she secretly hates Melanie, Scarlett loves society life in Atlanta. The war only really starts to impress on her mind as something of relevance when the Confederates begin to lose. The Yankee General Sherman’s destructive ‘March to the Sea’ through Georgia was the event that really put the nail in the coffin for the antebellum South; it is from this point onwards that we see Scarlett’s remarkable coming of age story begin as she fights to claw her way out of the poverty she has suddenly been plunged into.

History

Mitchell was born in Atlanta in 1900 and grew up on stories of the Civil War and Reconstruction from relatives that had lived through it all, making her extremely well-disposed to write such a novel. I was very impressed throughout by her level of historical detail and accuracy, all while maintaining a superb level of readability and shrewd commentary as the omniscient narrator.

Mitchell has been criticised for her portrayal of certain groups in GWTW, but in my opinion she doesn’t let anybody off the hook. For example, sexist comments made about the lesser mental capabilities of women often come from the female characters as well as the men, and is simply representative of what Scarlett’s generation would have been brought up to believe. Men don’t get an easy ride either – on the whole they are portrayed as impetuous and overly proud beings who secretly need the quiet sense of a woman to maintain them.

However, it is the portrayal of various racial groups that has come under the most scrutiny since the novel’s publication. Evidently, the issue of slavery was inextricably tied up in the American Civil War. It’s not key to the plot of the novel, but it’s an important backdrop. The motif of the faithful and devoted slave permeates GWTW via house slave characters like Mammy, Pork and Uncle Peter. GWTW is typical of southern plantation fiction in that it is written according to the viewpoint and values of the slaveholder, and so mostly depicts slaves as docile and happy. You may criticise this, but in many ways, it is a realistic depiction of white slaveholder mentality of the time. Furthermore, within the caste system that existed in the South, topped by the white planter class, house slaves were seen as an integral part of the wealthy white family and were almost respected more than groups like the poor whites. Scarlett and other characters frequently use the term ‘darky’ to refer to both familiar and unfamiliar slaves in GWTW. This is undeniably racist, but it often used as a term of endearment, revealing the interestingly paradoxical nature of racial intricacies in the South.

Mitchell stays true to this Southern racial hierarchy in emphasising that poor whites, field slaves and perceived insolent freedmen were together at the very bottom. Any racist comments made about slaves concerning a thieving, childlike or brutish nature are really only applied to this group. As a modern reader it can be quite shocking to read some of the offhand comments made about African-Americans and many have condemned their portrayal as perpetuating racist myths. Whether Mitchell wrote this way because she held those opinions or whether she was simply trying to be true to the time I do not know. Whatever the reason, I think it’s important that she wrote how she did because it means that irrefutable elements of American racial history have not been erased.

Protagonists / Coming of age

Of course, the main element of the story that captivates the reader is the intertwining journeys of Scarlett O’Hara and the dashing rogue Captain Rhett Butler. When they first meet at a society barbecue Scarlett is 16 and Rhett is 28. However, it is not until Scarlett moves to Atlanta that Rhett becomes of any importance to her and even then, she still believes herself in love with Ashley. Both protagonists are refreshingly different in the sense that they are unapologetically selfish, judgemental, arrogant, bitingly sarcastic and indifferent to the Confederate cause. Evidently these are not qualities revered by the South, so it is only with each other that Scarlett and Rhett can truly be themselves. In spite of myself, I liked them both a lot.

When the Civil War hardships begin, Scarlett is as ruthless as ever but this time for her own and her family’s survival, hinting at a change in her moral psyche no matter how much she begrudges herself for it. It is at this stage of the novel that we see Scarlett develop from a superficial teen to a strong, imperturbable woman. The immediate aftermath of the war is a harrowing part of GWTW to read as we see all the familiar characters plunged into uncertainty and desolation in a Georgia that has been decimated by the Union. Scarlett almost buckles under the weight of her newfound responsibilities more than once, but it is her aforementioned qualities that give her the gumption to eventually rise up again.

Even Rhett, who believed the Confederacy was a lost cause from the start, feels morally bound to enlist eight months before the end of the war meaning he is pretty absent from this part of the book.

Love

Saving the best until last – GWTW is known as ‘the classic love story’. It is one of the best and most emotional love stories I have read, but it is in no way classic. It is extremely frustrating as the reader to see the Scarlett and Rhett romance continue to not happen throughout the novel. It is clear that he is in love with her for years – among other things, he continues to put himself at risk coming to see her while working as a blockade runner and quietly making sure she is alright, despite the laddish bravado he keeps up. Scarlett often finds herself thinking about Rhett, but she doesn’t know why – it is at this point that you want to shake her and shout ‘because you love him of course!’

Eventually, Rhett asks her to marry him. Yes, I thought, this is the moment we’ve all been waiting for. Undoubtedly, their marriage is fun for a while. Scarlett finds him an interesting and devilish companion who is as wilful as herself, and he spoils her with whatever she likes. This is a screamingly obvious sign to the reader that he is attempting to make her realise her true feelings by indulging her every whim, but still her lingering teenage fantasy of Ashley clouds her vision.

They even have a child together, Bonnie, and there are so many moments where one of them is on the brink of expressing their true feelings before their Southern pride forces them to keep their mouths shut. It is not until a series of tragedies strike at the end of the novel that Scarlett realises how blind she has been. It is a great moment indeed when, aged 28, she can finally relinquish her fantasy of Ashley, which had been the albatross around her neck since she was 16.

I can say with confidence that I have never finished a book so feverishly as I did GWTW. Scarlett’s run home to tell Rhett how she feels seems to go on forever and I remember literally praying that he would still feel the same, despite all their recent struggles. When he eventually rejects her after a long and emotionally charged conversation, I felt as heart-broken and bereft as Scarlett. This is a tragedy on par with Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovers – if only she had only realised her feelings all those years ago, or if only Rhett’s intensely passionate true love could have held a bit longer before burning out completely, the climax of this 12-year tale would not have been so awfully sad. As the reader who could see it all along and was willing it to happen all throughout, the feeling of frustrated helplessness is almost too much to bear – and I’m not ashamed to say that I cried for a full hour after finishing it, and was thinking about it for much longer still.

Closing thoughts

Mitchell took the title Gone with the Wind from the poem Non Sum Qualis Eram Bonae sub Regno Cynarae by British poet Ernest Dowson.

I have forgot much, Cynara! gone with the wind,

Flung roses, roses riotously with the throng,

Dancing, to put thy pale, lost lilies out of mind …

Scarlett uses the phrase to wonder if Tara was still standing after Sherman’s March to the Sea, or if it had ‘gone with the wind that had swept through Georgia’. In this way, the title is a metaphor for the demise of the pre-Civil War way of life in the South.

In the poem, Dobson uses the phrase to indicate an erotic loss. He is expressing the regrets of someone who has lost their feelings for their old passion, Cynara, who in this context therefore represents a lost love. Undoubtedly, this is an allusion to Rhett’s love for Scarlett finally exhausting itself; so really Mitchell tells us the ending before we even begin reading. In fact, I was taken aback to discover that she wrote the ending first and then spent all those years writing the novel to build up to this heart-wrenching moment.

There is a slight glimmer of hope at the end in Scarlett vowing to win back Rhett’s heart, as she had won it before and held it for many years and the art of captivating men in general is something she mastered a long time ago. Her steely determination got her everything else she wanted in GWTW, and she believes it can do the same with Rhett.

Based on their enduring relationship, I don’t doubt that Scarlett and Rhett would reunite and finally have their happily ever after. This is what I am choosing to believe happens after the end of the novel, but Mitchell choosing to end it so ambiguously will always play on my mind.

This novel is one of those life-changing reads that will stay with me forever. It is thoroughly enjoyable despite the sadness of the ending and will consistently stir up every emotion within you. It is the sign of a great work of literature to be able to make a reader cry and think about the words long after finishing reading them, while also transporting you so easily back to an era long past with the vibrancy and accuracy of historical detail.

Gone with the Wind – 10/10!

Happy reading,

Imo x