Blog Nº 31

“I’ve been a Danish prince, a Texas slave-dealer, an Arab sheik, a Cheyenne Dog Soldier, and a Yankee navy lieutenant in my time, among other things, and none of ’em was as hard to sustain as my lifetime’s impersonation of a British officer and gentleman.”

Flashman and the Great Game

It is difficult to know how to start this blog – in a nutshell, this collection of stories is just brilliant, and has earned itself a place in my top 5 books of all time. This particular omnibus includes three of the series of novels entitled ‘The Flashman Papers’, and I’m already chomping at the bit to read the rest. The stories are the memoirs of the fictional character General Sir Harry Paget Flashman, VC, KCB, KCIE, who is slotted into a series of real historical events between 1839 to 1894.

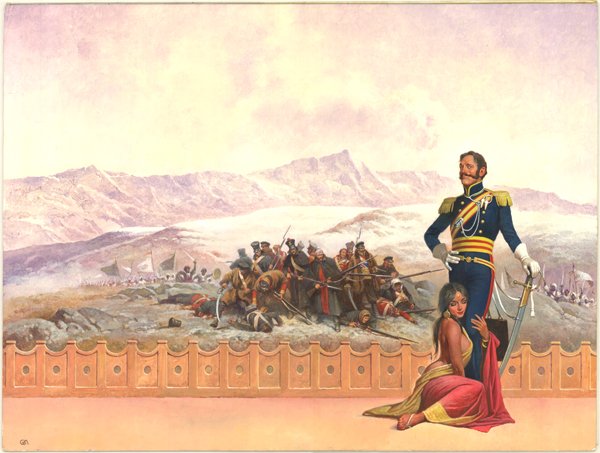

This edition contains the very first novel, Flashman (1969), which sees the young Harry Flashman, newly expelled from Rugby School, join the 11th Dragoons. With this regiment he is reluctantly sent off to fight in the first Anglo-Afghan War, where we first discover his extraordinary ability for self-preservation through any means necessary.

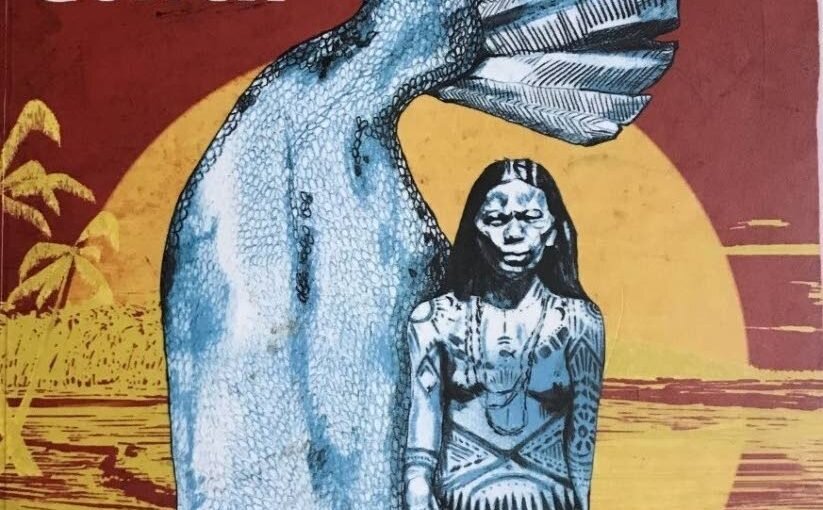

In Flash for Freedom! (1971), we reconvene with Flashman in his late 20s, where we find him pressganged into crewing on slave ship the Balliol College, hiding out in New Orleans, being on the run with an escaped slave and bumping into up and coming politician Abraham Lincoln.

Finally, in Flashman in the Great Game (1975), we are transported across to British India, in which Flashman finds himself spying for the British government, becoming enamoured with a ruthless Maharani and getting caught up in the brutal Sepoy Rebellion of 1857.

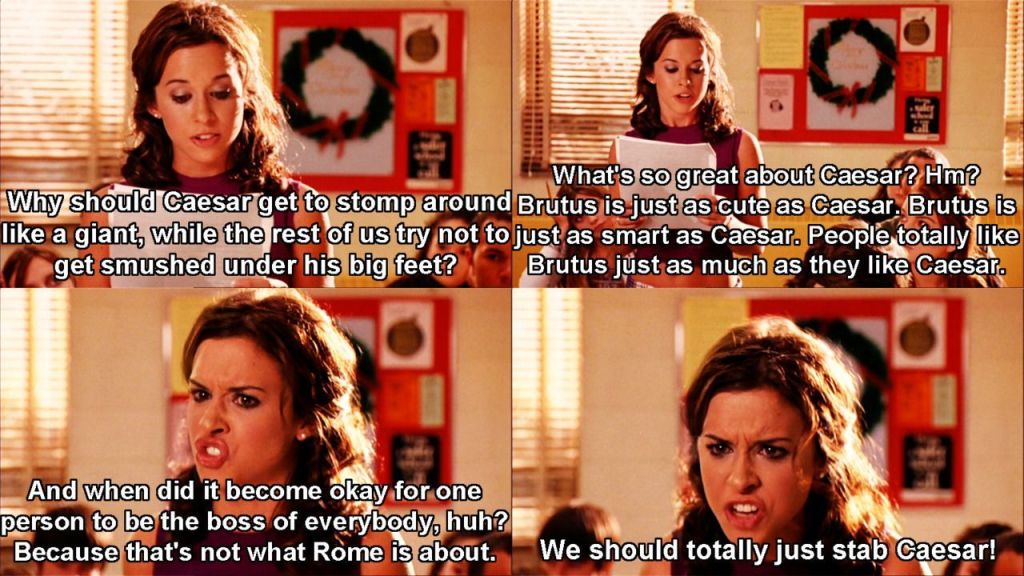

What makes these books so brilliant is the character of Flashman himself. Up until this point it would seem obvious to assume that ‘Flashy’ is a gallant military hero. In fact, he is a self-confessed rogue, scoundrel, liar, cheat, coward and womaniser, who in every instance is just trying to save his own skin, but happens to have the charm, wit and good luck to fool those around him that he is in fact the hero he appears to be. He will happily screw over those around him in pursuit of self-preservation and is entirely truthful in what he relays to the reader. And yet he is totally and utterly likeable. His honesty is refreshing and comical to read, but also when he tells of his exploits it really does seem like he escaped each situation in the only possible way. Flashman puts it all down to his heartlessness, but in many situations it does also show him as choosing duty to his country over personal feelings towards others. Of course, he would always do whatever it takes to survive, but quite often this supposed coward does have to act with extreme courage and intelligence simply in the interest of self-preservation. By the end, Flashman has almost become the hero he says that he isn’t, in spite of himself and his actions. Furthermore, though his behaviour is audacious, completely self-centred and deplorable, he is often the voice of sanity and reason in a world full of corruption, stupidity and false piety. His wit, sarcasm and pragmatism cuts through the craziness around him which is very entertaining to read. You are guaranteed to enjoy reading how Flashman romps his way through decades of Victorian history, and how through spectacular acts of spinelessness he manages to win military glory and nationwide respect.

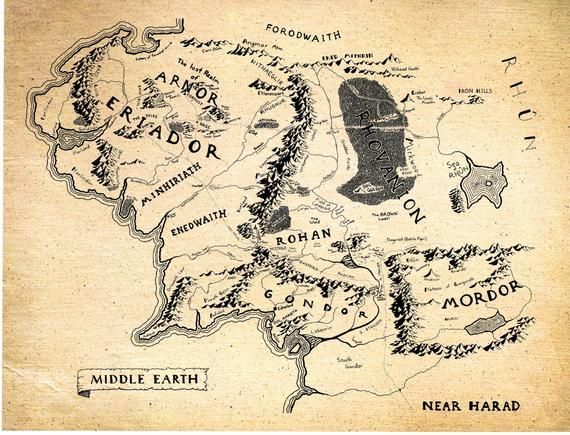

The character of Flashman is brought even more to life by Fraser’s unbelievably accurate replication of swaggering Victorian English, particularly when discussing his numerous exploits with various women throughout the books, which cements his reputation as a cad and a rake. In fact, Fraser’s accuracy in all elements of these books is something to be applauded. He manages to seamlessly insert Flashman and other fictional characters into real historical events without causing a ripple in the factual accuracy of the given moment. The way each battle or political event and the opinions surrounding them is relayed is so precise that you would not believe these books were written a century after they were set. On first publication, Fraser prefaced his novel with the discovery of the Flashman Papers at a house auction in Ashby, Leicestershire in 1965, and named himself only as the humble editor of the twelve instalments of the Flashman memoirs, which he called ‘packets’. He also surrounded the text with explanatory notes and scholarly additions such as maps and appendices, always using an editorial voice reminiscent of an assiduous bibliographer or archivist. Paired with the perceived accuracy and detail of the novel, almost half the initial book critics believed the Flashman novels to be real memoirs of a forgotten soldier in their reviews.

Fraser’s genius is making the historical accuracy of the Flashman stories come to life through the abounding use of comedy throughout. We have the aforementioned sarcastic, witty and outrageous voice of Flashman himself, but there is also sexual farce and intrigue, satirical dialogue and gallows humour. Fraser also expertly utilises syntax to provide humour throughout the novel, choosing just the right words to describe situations or people in an amusing manner. And yet, because he does not shy away from the awfulness, death and bloodshed encountered by Flashman and others throughout the series, the perceived reality of the memoirs remains intact. The books are undeniably entertaining and suspenseful, but the harsh historical realities of each period are illustrated truthfully. For example, Flash for Freedom! contains one of the most shocking and harrowing portrayals of the slave trade that I have ever read, while Flashman in the Great Game lays bare the horror of the Indian mutineers’ massacre of the wives and children of British military men during the Sepoy rebellion. Fraser has a knowledge of Victorian social and military history that is simply staggering for someone who is an amateur historian, and he manages to interweave this with a fictional narrative to create an astounding series of adventure, intrigue and mischief.

These books are an absolute joy to read – you will grow fond of the roguish Harry Flashman while getting a stellar education about important events of nineteenth-century history relating to the British Empire and antebellum America. In fact, you will almost be disappointed that Flashy is only fictional, as his life story really is one of the most astonishing out there.

Happy reading,

Imo x