Blog Nº 43

“When we press the thorn to our chest we know, we understand, and still we do it.”

I was so glad to be able to read The Thorn Birds for a second time for the blog. It is one of those novels that stays with you a long time after you finish reading it. Australia’s best-selling novel to date, this epic story spanning five decades is a tale of family, hard work and relationships set against the intoxicating backdrop of the beautiful but unforgiving New South Wales.

The central character of The Thorn Birds is Meggie Cleary, though several characters get their own sections. We begin in 1915 on Meggie’s 4th birthday. The Clearys – parents Paddy and Fee and their children Bob, Jack, Hughie, Stu, Meggie and Frank (Fee’s son from a previous relationship) – are a poor but hard-working family living in New Zealand. In 1921, Paddy’s wealthy sister Mary Carson offers Paddy a job on her huge sheep farming station in New South Wales, Australia. Drogheda, after its namesake in Ireland, is where most of the novel takes place.

It is here that we meet the ambitious young priest, Father Ralph de Bricassart, who is described as a ‘beautiful man’. He is a frequent visitor to Mary Carson in the hope that a large financial bequest from her will see him rise up in the Catholic Church and freed from the remote parish of Gillanbone, not far from Drogheda. He immediately develops a fondness for Meggie, and their complex relationship over the years is central to the novel.

Across the fifty-year span of The Thorn Birds the Clearys encounter birth, death, marriage, heartbreak, separation and the untamed might of the Australian wilderness in this truly absorbing novel.

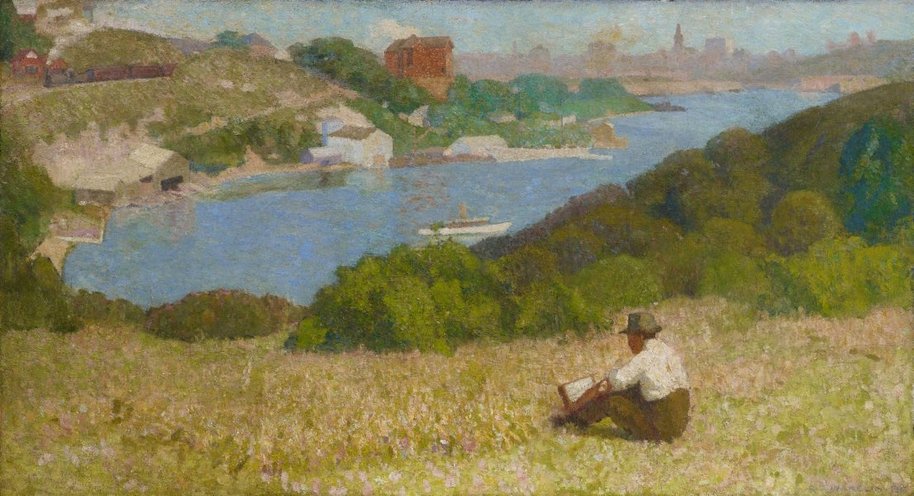

A standout feature of The Thorn Birds for me are the descriptions of the Australian landscape. Whether it’s tumbling hibiscus and Bougainvillea, ghost gum and bottle trees standing tall or the endlessly sprawling paddocks of Drogheda, it is hard not to be mesmerised by such a rich environment. It also becomes very apparent how much humans are at the mercy of nature. Across the novel we see how drought and heat can cripple a community, while intense torrents of rain can be relentless all wet season. During one tragic moment, one strike of lightning engulfs much of Drogheda in a blazing fire, causing loss and heartache for all the Clearys. The environmental aspect of the novel emphasises that though it is beautiful, the kind of life led by the Clearys is neither gentle nor easy.

The novel’s central storyline is the relationship between Meggie and Ralph. When they meet, Meggie is nine years old and Ralph is twenty-seven. There is an immediate chemistry between them; Meggie is instantly enchanted by Ralph, while Ralph becomes extremely infatuated with and protective of her. As Meggie grows into womanhood, their relationship grows more complex. It is quite clear that Ralph desires a sexual and romantic relationship with Meggie, but his vow of celibacy as a priest forbids him from pursuing this. Meggie has been in love with Ralph in one form or another since her childhood, and this also becomes a romantic and sexual desire in her late teens.

When I first read the novel several years ago, I think I was more taken with the common view that their love story was tragically romantic. Ralph is consistently described as a very handsome, kind man who even for the love of his life will not abandon his vow. For many years Meggie will not give any other man the time of day and has dreamed of only Ralph since her childhood.

However, upon second reading I found the relationship to be much more disturbing. What is abundantly clear to me is that Ralph de Bricassart, an adult for the entire story, manipulates Meggie Cleary from her childhood for an eventual sexual relationship once both are adults. During their first time having sex, Ralph admits to himself that he groomed or “molded” Meggie all along, albeit unconsciously.

“Truly she was made for him, for he had made her; for sixteen years he had shaped and molded her without knowing that he did, let alone why he did. And he forgot that he had ever given her away, that another man had shown her the end of what he had begun for himself, had always intended for himself, for she was his downfall, his rose; his creation.”

Father Ralph de Bricassart

The Thorn Birds was written in the 1970s and the focus is on a romanticised struggle between Ralph’s duty to the church and his feelings towards Meggie as a mere mortal man. The repeated emphasis on Ralph’s handsomeness and his rise up the church portrays him as being alluring and forbidden – it is playing into the trope of priests being fetishized due to their celibacy. Meggie’s lifelong love and pursuance of Ralph could also be seen as enduringly romantic and something to root for.

However, through the modern lens it is difficult to see it this way, particularly given the numerous stories that have been unearthed about sexual abuse within the Catholic church. The idea of fetishising a priest these days would therefore be wholly unusual. The large age gap also raises concerns for the modern reader. Meggie’s entire misguided idea of what love is, is based on Ralph. From girlish daydreams to repeated attempts to get him to break his vow. Ralph does not instil appropriate boundaries with her when she is an impressionable child; he is overbearingly affectionate, protective and it is something that would not be acceptable in today’s society.

Despite this, The Thorn Birds remains a captivating and emotionally charged novel, with every character gaining the reader’s sympathy, pity and disdain at various points throughout the story. I would absolutely recommend this novel – it is an unputdownable epic novel.

Happy reading,

Imo x