Blog Nº 33

“Mistrust all men, and slay him whom thou mistrustest overmuch; and as for women, flee from them, for they are evil, and in the end will destroy thee.”

She is without a doubt an extraordinary novel, one which will leave you deep in thought for days after finishing it. Haggard uses the English language in a thoroughly captivating way to tell this tale of myth, imperialism, horror and fascination, which has remained so popular with readers that it has never gone out of print since its first release over 130 years ago.

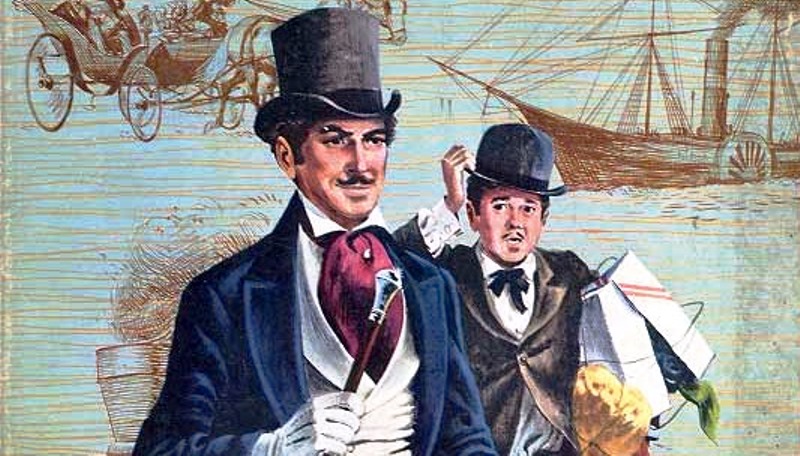

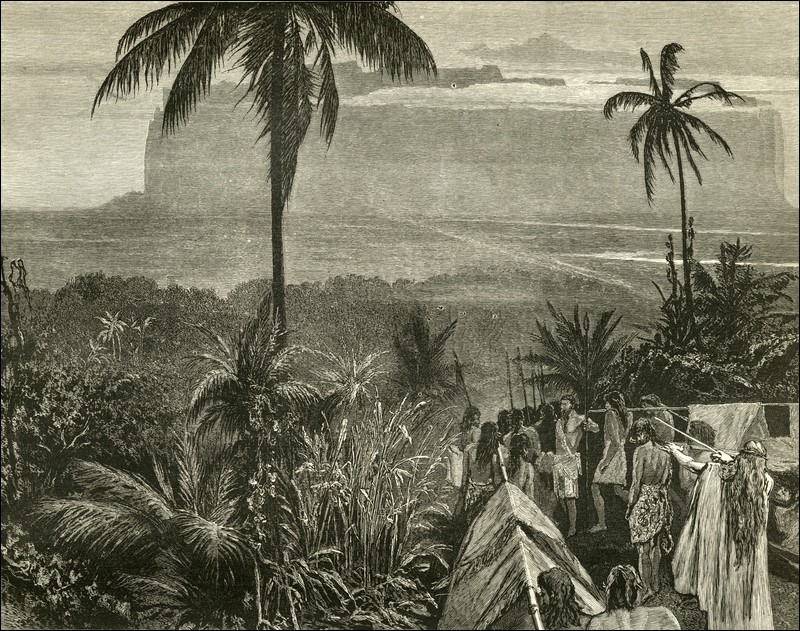

The novel is narrated by protagonist Horace Holly, and tells the tale of how he, a Cambridge professor, and his ward Leo Vincey came to be in the presence of Ayesha, the mysterious white queen of a Central African tribe. Her full title, She-who-must-be-obeyed, is a testament to how she can at once mesmerise with her eternal beauty and magical powers, but also be cruel and manipulative whenever the mood takes her. Holly and Leo’s journey to her hidden realm – which they are unsure is even real because it’s based on a 2,000-year-old quest – sees them battle shipwreck, fever, starvation and cannibals all to reach the goal of finding She. Both men are at once horrified and entranced by Ayesha, symbolising her as one of the most compelling and ambivalent figures in Western mythology – a female who is both monstrous and desirable, and without a doubt, more deadly than the male.

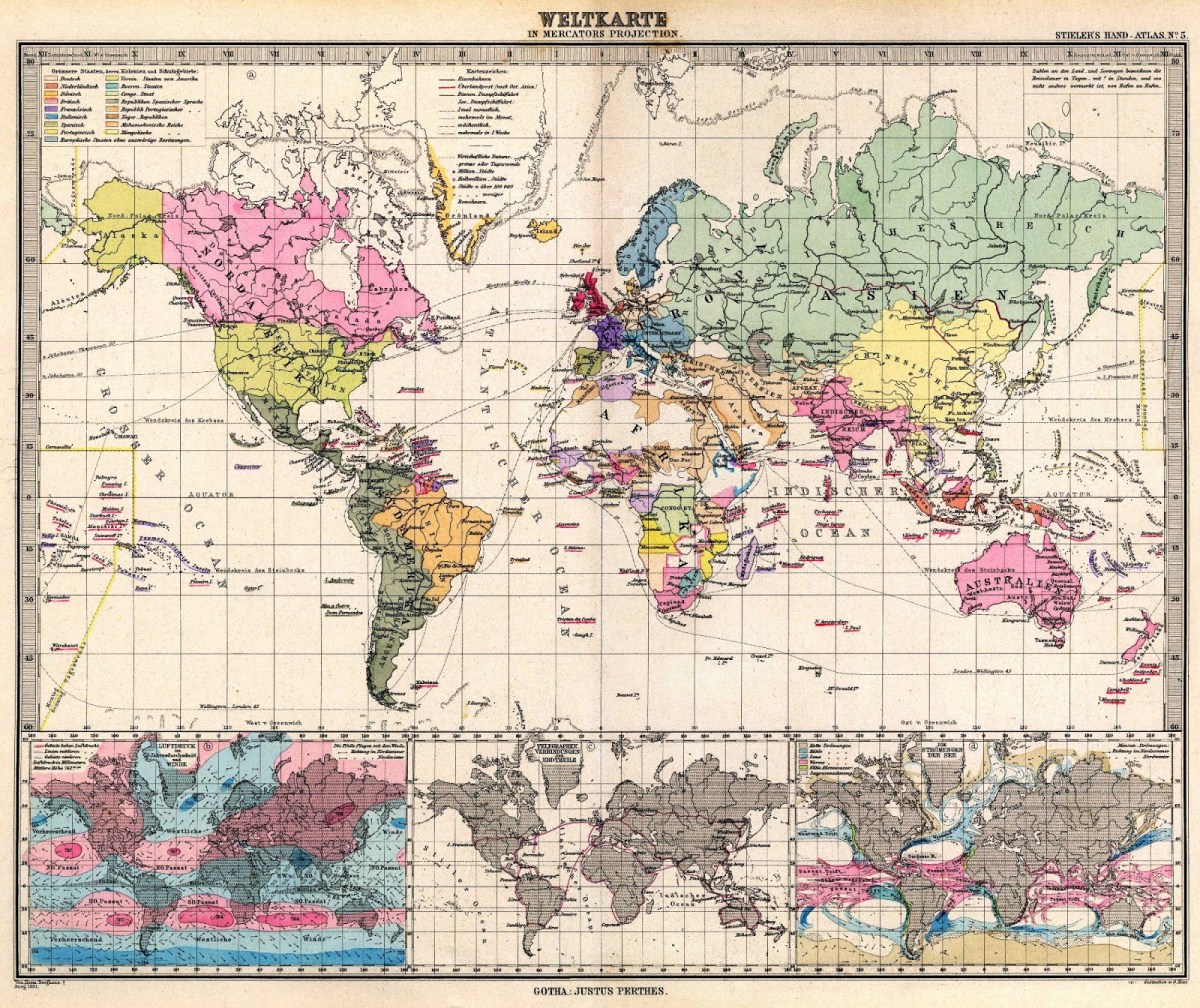

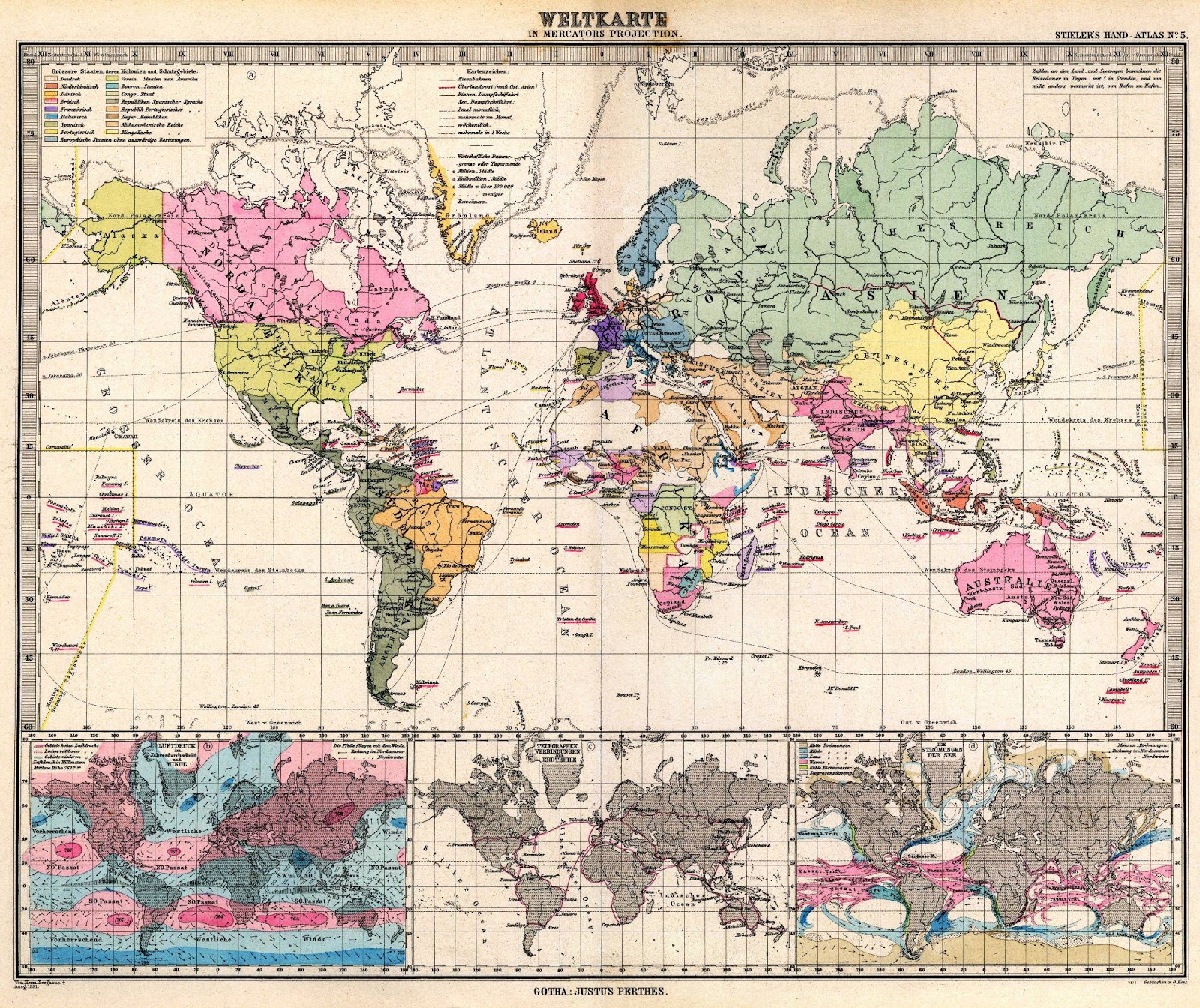

She is a vivid example of imperialist literature. As such, it embraces many hallmarks typical of this genre including ideas of racial and cultural hierarchy that were popular in the late Victorian period and adventuring to a ‘lost world’ (Haggard developed many conventions of this genre), in this case deep in the wild interior of Africa. Before writing this novel Haggard lived in South Africa for seven years, working in a very senior position of the British colonial administration, and he was heavily inspired by his time there when writing She. The sense of adventure in this novel is intoxicating, and since its publication She has been popular with readers across the age and gender spectrum. Like Holly and Leo, we are intrigued by this secret tribe living in an arresting, undiscovered pocket of land in Central Africa, and even more intrigued as to how they are so entirely ruled over by an eternal, beautiful, magical queen who commands power, fear and obedience with as little as a title, She-who-must-be-obeyed.

Significantly, She provides us with an interesting exploration of themes including female authority and womanhood. Some scholars have noted that the publication of She coincided with Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubliee and suggested that She is an ominous literary tribute to the Queen on her 50 years on the throne. Both women are also chaste and devoted to one man – Victoria to Albert and Ayesha to Kallikrates, an ancient lover for whom she has waited patiently for 2,000 years to return to her. While Victoria is seen as a benign figure, Ayesha embodies late Victorian fears of a feminist movement desiring absolute female independence and absolute control over men. Anxiety over all-consuming female authority is present throughout the novel, particularly when both Holly and Leo – who represent ‘superior’ male intellect and physicality respectively – quickly fall under her will. Even their rational minds and Holly’s self-confessed misogyny are no defence against Ayesha, and they both worship her “as never woman was worshipped”. Even in the tribe that She rules over, women are respected and not subservient to men and there is no such thing as monogamy. Women select their partners, and they can have as many as they like. In one sense this is positive, because we see women taking control of their lives in a time where they were largely oppressed and thought of as the inferior sex. However, Ayesha also falls into the category of seductive femme fatale, which is a part of a centuries-old tradition of Western male sexual fantasy that includes other characters such as Homer’s Circe, Flaubert’s Salammbô, and Shakespeare’s Cleopatra.

In conclusion She is a novel which will take hold of you, as it has taken hold of many generations since its publication in 1887; it is not only the characters that become fascinated by the unknowable She-who-must-be-obeyed. Experience romance, adventure, danger, horror and get a intriguing insight into the Victorian imperial mindset with this astonishing work of fiction.

Happy reading,

Imo x