Blog Nº 8

“Ain’t nothing in this world just for the taking… A man got to pay a fair price for taking… Matter of give a little, take a little” – Thomas Blackwood

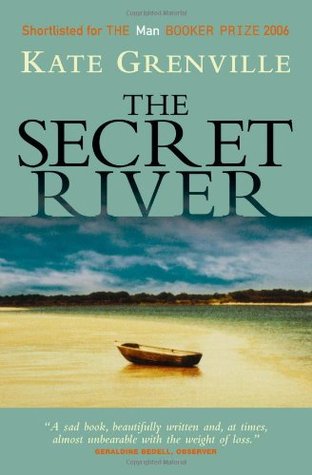

As a British colonial history enthusiast, I found The Secret River deeply thought-provoking in its portrayal of the settlement of Australia by British convicts sentenced to transportation in the nineteenth century. I actually read this novel about a year ago, but I recently went to see the critically acclaimed Sydney Theatre Company’s stage adaptation of it at the National Theatre. Unlike most of the critics, I was left somewhat disappointed by the stage version, so I was inspired to write this blog in the format of ‘novel vs play’ (hence the longer post).

Sadly, the flaws in the play begin in the first scene; astoundingly, it opens with lead character William Thornhill and his family arriving at their secluded 200 acre plot of land up the Hawkesbury River in New South Wales, which he has persuaded his wife Sal that once settled and cultivated, will make them their fortune. I had to do a double take; where indeed was the journey up to this point? Arriving at ‘Thornhill’s Point’ as it comes to be known, is a landmark event in the plot and yet the exclusion of all that comes before completely lessens the impact of this moment. We are missing the whole first section of Grenville’s novel, detailing William’s Dickensian poverty-stricken upbringing in Southwark, London and his constant struggle to rise above his lowly class and status. We miss his marriage to Sal and how an icy winter bars him from working as a boatman, and how this change in fortunes forces him to turn to stealing. He is caught and sentenced to transportation along with Sal, his son Willie, and unborn child.

And then, it is not as if William could simply walk onto a 200 acre plot of land on arrival. He arrives a convict, and over 12 months works tirelessly in the colony until he can buy his freedom. Here we see a crucial change in William’s attitude; he is befriending those above his station, he is mimicking their dress and manners, and most importantly he begins to feel a personal sense of authority and superiority over his peers. The family’s move to Thornhill’s Point is not easy; Sal’s heart is set on returning to London, and agrees only on the basis that they will stay five years maximum to make their fortune before going ‘home’. William agrees, but with his newfound ‘status’ it is clear he has other ideas.

The play erases some very crucial plot and character development points here and this causes a problem for what it chooses to leave in. For example, Sal’s daily tally for how many days they have been there, her constant pining for London and singing of folk songs like ‘The Bells of St Clements’ doesn’t really make sense without the backstory. The play gives William his superior attitude over his peers, but it has not altered his dress, manner or speech from destitute London beggar so it appears confusing and inconsistent, and again nonsensical without the context.

In the stage version, we are thrown straight into the Thornhills settling their land and the encounters they begin to have with the Aboriginal population. The portrayal of the Aboriginals is something the play should be applauded on. As the novel is told from the perspective of the Thornhills, naturally we are not given much insight into the lives or claims on the land of the Aboriginals. Onstage, we see them living their lives and interacting, lessening the idea of them being the ‘other’ to be feared in the eyes of the audience. The cast playing the Dharug tribal family are Aboriginal performers, and the music and staging was conceived in collaboration with Aboriginal artists, so the play has done well in terms of representation and diversity. Furthermore, the actors playing the Thornhills have ghoulish white paint on their bodies and faces; I thought this was a very effective way of demonstrating how strange and how freakishly white settlers must have looked to Aboriginal peoples, showing that white skin is only ‘normal’ in the eyes of those who have white skin themselves.

The interactions between the Thornhills (plus other white settlers along the river) and the Dharugs are done well; they are sometimes tense, sometimes curious, sometimes funny and always slightly cautious. The prejudice-free childhood friendship between Thornhill’s youngest son Dick and an Aboriginal boy of around the same age is heartwarming to see. This brings me to the other fatal flaw the play has made in terms of adapting the plot. In the novel, following the settlers’ massacre of the Aboriginals (more on this below), Dick cannot forgive his father for his role in this crime. He leaves his family and goes to live upriver with Blackwood, a settler who had already made a life with an Aboriginal woman. He never speaks to his family again and to me this plot point is very effective in showing the stark horror of what the settlers had done, i.e. of what much of colonial settlement was. Of course, in the book the characters age, so Dick is old enough to understand what has happened and make this choice. The actors/characters do not age in the play, which is a shame because the full impact of the massacre in terms of betrayal is not realised. That is, the settlers and Aboriginals were neighbours for years before this assault, whereas in the play their relationship appears much more brief.

However, the massacre itself was staged extremely well. It was emotional, heart-wrenching and almost too difficult to watch. Each Aboriginal was cut down in slow motion, one by one, with the white characters blowing powder from their hands to represent gunshots. Paired with the music and lighting, this was a raw and guilt-tripping depiction of colonial violence. The music and lighting were superb throughout the production in fact, and really helped bring out the setting and emotion of key scenes.

To conclude then, if I were Kate Grenville I’m not sure I would be especially happy with this production. I think her novel is excellent (so I would definitely recommend reading it), and I appreciate what the play tries to do in terms of bringing her moral messages about nineteenth-century colonial activity in Australia to light. But, the careless and almost lazy adaptation of the plot in this production takes away from the progressive steps it takes to do this. It’s an excellent story that needs to be told, but I think in this instance it could have been told much better (sorry, script-writers).

Happy reading,

Imo x